For reasons that I probably do not myself fully understand, I am endlessly intrigued by discussions of the ever elusive state of being we call authenticity. At least part of the intrigue lies in how a discussion of authenticity can ensnare within itself philosophical, sociological, technological, and even religious considerations. It makes for lively and stimulating discussion in other words. Authenticity talk is intriguing as well because it may be under its guise that the ancient debate about what constitutes a good life and the venerable quest to “know thyself” survive today.

For reasons that I probably do not myself fully understand, I am endlessly intrigued by discussions of the ever elusive state of being we call authenticity. At least part of the intrigue lies in how a discussion of authenticity can ensnare within itself philosophical, sociological, technological, and even religious considerations. It makes for lively and stimulating discussion in other words. Authenticity talk is intriguing as well because it may be under its guise that the ancient debate about what constitutes a good life and the venerable quest to “know thyself” survive today.

Both of these considerations also suggest a serious difficulty presented by authenticity talk: the word authenticity, as it is commonly used, masks a complex and diverse set of concepts. This complexity and diversity threatens to introduce a slippery equivocation into what might otherwise be well-intended conversations and debates. At least this has been my experience. But then again, discussing what exactly authenticity is is part of what makes such discussions lively and interesting.

My own thinking about authenticity is sporadic and owes more to serendipity than to any conscientious scholarly endeavor. For example, most recently, from no particular quarter, the following question formulated itself in my mind: What is the problem to which authenticity is the answer?

There is nothing particularly insightful about this question, but it did get me thinking about the whole set of ideas from a different angle. The meandering mental path that subsequently unfolded led me to identify this problem as some sort of psychic rupture or dissonance. We don’t think of authenticity at all unless we think of it as a problem, and it presents itself as a problem at the very time it enters our conscious awareness. It is a problem tied to our awareness of ourselves as selves.

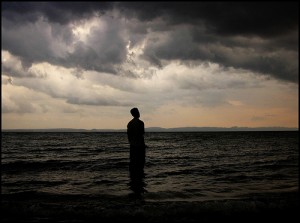

There are many interesting paths that unfold from that point, but I want to offer this one subsequent stab at defining what we (sometimes) mean by authenticity: Authenticity is a seamless continuity between the self, time, and place. It is a sense of complete at-homeness in the world. For this reason, then, we might see nostalgia as another manifestation of the problem of authenticity. Nostalgia — first in its literal sense as longing for spatial home, and then its more contemporary form as longing for a home in time — is a symptom of the rupture in the continuity between self, time, and place that generates an awareness of the self as a problem to be solved, an awareness that constitutes the problem of authenticity.

Framing the discussion as matter of at-homeness (or a lack thereof) recalled to my mind the work of the medical doctor turned novelist cum philosopher, Walker Percy. Percy went from being a diagnostician of physical maladies to one of existential maladies. With his acute Pascalian eye, Percy made a literary career of diagnosing the modern self’s inability to understand itself. This was the theme of his send-off of the self-help genre, Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book.

Percy chose the following passage from Nietzsche as an epigraph for Lost in the Cosmos:

“We are unknown, we knowers, to ourselves … Of necessity we remain strangers to ourselves, we understand ourselves not, in our selves we are bound to be mistaken, for each of us holds good to all eternity the motto, ‘Each is the farthest away from himself’—as far as ourselves are concerned we are not knowers.”

A little further on, in his inventory of possible “selfs” (or should that be “sevles”), Percy offered this description of the lost self:

“With the passing of the cosmological myths and the fading of Christianity as a guarantor of the identity of the self, the self becomes dislocated, … is both cut loose and imprisoned by its own freedom, yet imprisoned by a curious and paradoxical bondage like a Chinese handcuff, so that the very attempts to free itself, e.g., by ever more refined techniques for the pursuit of happiness, only tighten the bondage and distance the self ever farther from the very world it wishes to inhabit as its homeland …. Every advance in an objective understanding of the Cosmos and in its technological control further distances the self from the Cosmos precisely in the degree of the advance—so that in the end the self becomes a space-bound ghost which roams the very Cosmos it understands perfectly.”

Percy was writing in 1983. Centuries earlier, St. Augustine wrote, “I have been made a question to myself.” The problem of authenticity is much older than we sometimes realize. Perhaps we might say that it is a perpetually possible problem that is more or less actualized given certain historical or psychological conditions. Perhaps the problem of authenticity is not a problem at all, but as C.S. Lewis once wrote of nostalgia, the “truest index of our real situation.”