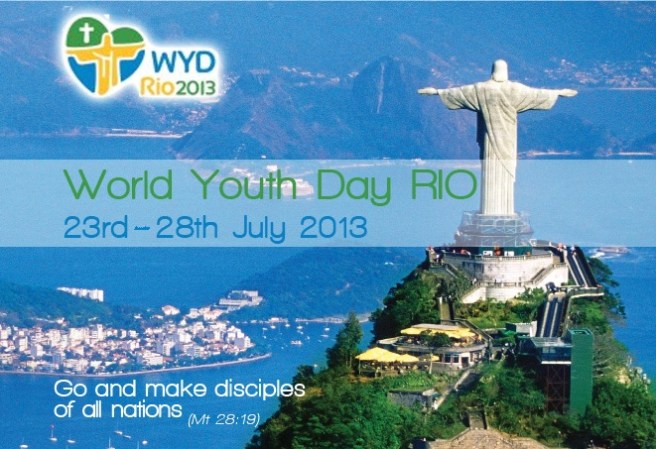

For the first time since 1517, when Martin Luther kicked off the Protestant Reformation, indulgences are in the news. As the start of the Roman Catholic Church’s 28th annual World Youth Day in Rio de Janeiro drew near, it was widely reported that Pope Francis had decreed the granting of special indulgences for those who took part in the event. A decree of this sort would not ordinarily garner any media attention, but this particular decree contained an unprecedented measure. Indulgences were offered even to those who followed the event on social media.

Perhaps a little background is in order here. In Roman Catholic theology, Purgatory is where those who are ultimately on their way to Heaven go to satisfy all of the temporal punishment they’ve got coming and otherwise get spiritually prepared to enter Heaven. This is where indulgences come in.

The Church, as a conduit of God’s grace, may issue indulgences to reduce one’s time in Purgatory. Indulgences are premised on the notion that while most of us end up in the red when the moral account of our lives is taken, saints, martyrs, the Virgin, etc. ended up in the black. Their abundance of moral virtue constitutes a Treasury of Merit on which the Church can draw in order to help out those who are still paying up in Purgatory. Indulgences, then, are not, as they are sometimes portrayed in the press, a “get out of Hell free” card. They are more like a fast-pass through Purgatory.

That early modern religious, political, and cultural revolution we call the Protestant Reformation was kicked off when a German monk named Martin Luther posted 95 Theses for disputation on the door of a church in Wittenberg. Luther took aim at the practice of selling indulgences to fill the Church’s more literal treasury. He was particularly scandalized by the abuses of the notoriously unscrupulous Johann Tetzel. Think of Tetzel as a late medieval version of the worst stereotype of a contemporary televangelist. Luther set out to shut Tetzel and his ilk down, and the rest, as they say, is history.

While the practice of selling indulgences was banned by the Church shortly after Luther’s day, the Catholic Church still offers indulgences for particular works of piety. And that brings us back to Francis’ offer of indulgences to those who participate in World Youth Day celebrations. Here is the portion of the decree that has made a story out of these indulgences:

Those faithful who are legitimately prevented may obtain the Plenary Indulgence as long as, having fulfilled the usual conditions — spiritual, sacramental and of prayer — with the intention of filial submission to the Roman Pontiff, they participate in spirit in the sacred functions on the specific days, and as long as they follow these same rites and devotional practices via television and radio or, always with the proper devotion, through the new means of social communication; …

The “new means of social communication” have been widely reduced to Twitter in accounts of this story. Following the Pope’s tweets (@Pontifex) during the week is one way of virtually participating in the event. The faithful may also watch live streaming video through web-portals set up by the Vatican or keep up on Facebook and Pinterest.

Claudio Maria Celli, president of the pontifical council for social communications, was quick to clarify the intent of the decree. “Get it out of your heads straight away,” Celli explained to the media, “that this is in any way mechanical, that you just need to click on the internet in a few days’ time to get a plenary indulgence.”

As the text of the decree makes clear, the “usual conditions” apply. Believers must be properly motivated and they must see to the ordinary means of grace offered by the Church: confession, penance, and prayer. And there’s also that line, almost entirely neglected in media reports, about being “legitimately prevented” from attending. But Celli seemed particularly determined to prevent any misunderstanding on account of the inclusion of digital media:

You don’t get the indulgence the way you get a coffee from a vending machine. There’s no counter handing out certificates. To put it another way, it won’t be sufficient to attend the mass in Rio online, follow the Pope on your iPad or visit Pope2You.net. These are only tools that are available to believers. What really matters is that the Pope’s tweets from Brazil, or the photos of World Youth Day that will be posted on Pinterest, should bear authentic spiritual fruit in the hearts of each one of us.

Protestants are usually taken to be more technologically savvy than the Catholic Church. After all, while the Catholic Church was weighing the moral hazards of the printing press, Protestants took to it enthusiastically and used it to spread their message across Europe. It is also true that American evangelicals have been especially keen on appropriating new media to spread the good news. As Henry Jenkins, a scholar of new media, put it,

Evangelical Christians have been key innovators in their use of emerging media technologies, tapping every available channel in their effort to spread the Gospel around the world. I often tell students that the history of new media has been shaped again and again by four key innovative groups – evangelists, pornographers, advertisers, and politicians, each of whom is constantly looking for new ways to interface with their public.

But this way of telling the story, centered as it is on print and the communication of a message, may be obscuring the fuller account of the Catholic Church’s relationship to media technology. It may be, in fact, that the Catholic Church is well-positioned, given its particular forms of spirituality, to flourish in an age of digital media.

Making that case convincingly is a book-length project, but, allowing for some rough-and-ready generalizations, here’s the shorter version. It starts with recognizing that Francis’ decision to extend indulgences to those who are not physically present in Rio is not without precedent. This strikingly 21st century development has a medieval antecedent.

If you’ve ever visited a Roman Catholic Church, you’ve likely seen the Way of the Cross (sometimes called the Stations of the Cross): a series of images depicting scenes from the final hours of Jesus’ life. There are fourteen stations including, for example, his condemnation before Pilate, the laying of the cross on his shoulders, three falls on the way to the site of the crucifixion, and culminating with his body being laid in the tomb. Catholics may earn indulgences by prayerfully traversing the Way of the Cross.

What makes this a precedent to Francis’ decree is that the Way of the Cross represented by images – carved, painted, sculptured, engraved, etc. – in local churches was a way of making a virtual pilgrimage to these same places in Jerusalem. Since at least the fourth century, Christians prized a visit to the Holy Land, but, as you can easily imagine, that journey was not cheap or comfortable, nor was it entirely safe. By the late medieval period, the Way of the Cross was appearing in churches across Europe as a concession to those unable to travel to Jerusalem.

While the precise history of the Way of the Cross is a bit murky, it is clear that the regularizing of the virtual pilgrimage transpired under the auspices of the Franciscan Order. This is not entirely surprising given the Franciscan Order’s traditional care for the poor, those least likely to make the physical pilgrimage. It also makes it rather fitting that it is Pope Francis – who took his papal title from St. Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscan Order – who first legitimized social media as a vehicle of indulgences.

What’s interesting about this connection is that Catholic theology had grappled with the notion of virtual presence long before the advent of electronic or digital media. And this leads to one of those egregious generalizations: Protestant piety was wedded to words (printed words particularly) and while Catholic piety was historically comfortable with a wider range of media (images especially).

This means that Protestants have understood media primarily as a means of communicating information, and Catholics, while obviously aware of media as a means of communicating information, have also (tacitly perhaps) understood media as a means of communicating presence. Along with the Way of the Cross, consider the prominence of images, icons, and statues of Jesus, Mary, and the saints in Catholic piety. These images, whatever shape they take, are reverenced in as much as they mediate the presence of the “prototypes” which they represent.

Without claiming that the printed book created Protestantism, we could argue that in a media environment dominated by print, Protestant forms of piety enjoy a heightened plausibility. Print privileges message over presence. But high bandwidth digital media, combining audio and image, have become more than conduits of information, they increasingly channel presence and may thus be more hospitable to Catholic spirituality. Conversely, digital media may present intriguing challenges to traditional forms of Protestant spirituality.

It’s not surprising, then, that Pope Francis has seen fit to sanction digital media as legitimate tools of spirituality for Catholics. As Fr Paolo Padrini, a Catholic scholar of new media, put it, digital media allow for “Sharing, acting in unison, despite the obstacle of distance. But it will still be real participation and that is why you will obtain the indulgence. Above all because your click will have come from the heart.”