David Gelernter, 2013:

“And today, the most important function of the internet is to deliver the latest information, to tell us what’s happening right now. That’s why so many time-based structures have emerged in the cybersphere: to satisfy the need for the newest data. Whether tweet or timeline, all are time-ordered streams designed to tell you what’s new … But what happens if we merge all those blogs, feeds, chatstreams, and so forth? By adding together every timestream on the net — including the private lifestreams that are just beginning to emerge — into a single flood of data, we get the worldstream: a way to picture the cybersphere as a whole … What people really want is to tune in to information. Since many millions of separate lifestreams will exist in the cybersphere soon, our basic software will be the stream-browser: like today’s browsers, but designed to add, subtract, and navigate streams.”

E. M. Forster, 1909:

“Who is it?” she called. Her voice was irritable, for she had been interrupted often since the music began. She knew several thousand people, in certain directions human intercourse had advanced enormously.

But when she listened into the receiver, her white face wrinkled into smiles, and she said:

“Very well. Let us talk, I will isolate myself. I do not expect anything important will happen for the next five minutes-for I can give you fully five minutes …”

She touched the isolation knob, so that no one else could speak to her. Then she touched the lighting apparatus, and the little room was plunged into darkness.

“Be quick!” She called, her irritation returning. “Be quick, Kuno; here I am in the dark wasting my time.”

[Conversation ensues and comes to an abrupt close.]

Vashti’s next move was to turn off the isolation switch, and all the accumulations of the last three minutes burst upon her. The room was filled with the noise of bells, and speaking-tubes. What was the new food like? Could she recommend it? Has she had any ideas lately? Might one tell her one”s own ideas? Would she make an engagement to visit the public nurseries at an early date? – say this day month.

To most of these questions she replied with irritation – a growing quality in that accelerated age. She said that the new food was horrible. That she could not visit the public nurseries through press of engagements. That she had no ideas of her own but had just been told one-that four stars and three in the middle were like a man: she doubted there was much in it.

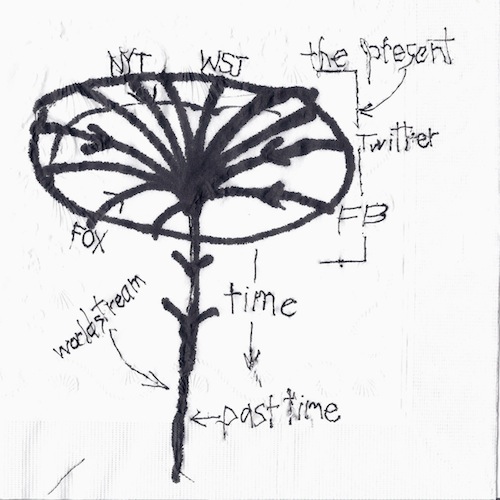

When I read Gelernter’s piece and his world-stream metaphor (illustration below), I was reminded of Forster’s story and the image of Vashti, sitting in her chair, immersed in cacophonic real-time stream of information. Of course, the one obvious difference between Gelernter’s and Forster’s conceptions of the relentless stream of information into which one plunges is the nature of the interface. In Forster’s story, “The Machine Stops,” the interface is anchored to a particular place. It is an armchair in a bare, dark room from which characters in his story rarely move. Gelernter assumes the mobile interfaces we’ve grown accustomed to over the last several years.

In Forster’s story, the great threat the Machine poses to its users is that of radical disembodiment. Bodies have atrophied, physicality is a burden, and all the ways in which the body comes to know the world have been overwhelmed by a perpetual feeding of the mind with ever more derivative “ideas.” This is a fascinating aspect of the story. Forster anticipates the insights of later philosophers such as Merleau-Ponty and Hubert Dreyfus as well as the many researchers helping us understand embodied cognition. Take this passage for example:

You know that we have lost the sense of space. We say “space is annihilated”, but we have annihilated not space, but the sense thereof. We have lost a part of ourselves. I determined to recover it, and I began by walking up and down the platform of the railway outside my room. Up and down, until I was tired, and so did recapture the meaning of “Near” and “Far”. “Near” is a place to which I can get quickly on my feet, not a place to which the train or the air-ship will take me quickly. “Far” is a place to which I cannot get quickly on my feet; the vomitory is “far”, though I could be there in thirty-eight seconds by summoning the train. Man is the measure. That was my first lesson. Man”s feet are the measure for distance, his hands are the measure for ownership, his body is the measure for all that is lovable and desirable and strong.

But how might Forster have conceived of his story if his interface had been mobile? Would his story still be a Cartesian nightmare? Or would he understand the danger to be posed to our sense of time rather than our sense of place? He might have worried not about the consequences of being anchored to one place, but rather being anchored to one time — a relentless, enduring present.

Were I Forster, however, I wouldn’t change his focus on the body. For isn’t our body and the physicality of lived experience that the body perceives also our most meaningful measure of time? Do not our memories etch themselves in our bodies? Does not a feel for the passing years emerge from the transformation of our bodies? Philosopher Merleau-Ponty spoke of the “time of the body.” Consider Shaun Gallagher’s exploration of Merleau-Ponty’s perspective:

“Temporality is in some way a ‘dimension of our being’ … More specifically, it is a dimension of our situated existence. Merleau-Ponty explains this along the lines of the Heideggerian analysis of being-in- the-world. It is in my everyday dealings with things that the horizon of the day gets defined: it is in ‘this moment I spend working, with, behind it, the horizon of the day that has elapsed, and in front of it, the evening and night – that I make contact with time, and learn to know its course’ …”

Gallagher goes on to cite the following passage from Merleau-Ponty:

“I do not form a mental picture of my day, it weighs upon me with all its weight, it is still there, and though I may not recall any detail of it, I have the impending power to do so, I still ‘have it in hand.’ . . . Our future is not made up exclusively of guesswork and daydreams. Ahead of what I see and perceive . . . my world is carried forward by lines of intentionality which trace out in advance at least the style of what is to come.”

Then Gallagher adds, “Thus, Merleau-Ponty suggests, I feel time on my shoulders and in my fatigued muscles; I get physically tired from my work; I see how much more I have to do. Time is measured out first of all in my embodied actions as I ‘reckon with an environment’ in which ‘I seek support in my tools, and am at my task rather than confronting it.'”

That last distinction between being at my task rather than confronting it seems particularly significant, especially as it involves the support of tools. Our sense of time, like our sense of place, is not an unchangeable given. It shifts and alters through technological mediation. Melvin Kranzberg, in the first of his six laws of technology, reminds us, “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” Our technological mediation of space and time is never neutral; and while it may not be “bad” or “good” in some abstract sense, it can be more or less humane, more or less conducive to our well-being. If the future of the Internet is the worldstream, we should perhaps think twice before plunging.