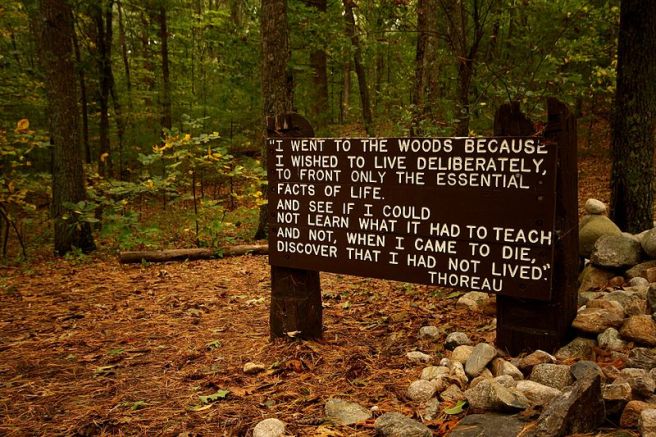

Long before the Internet and the smartphone, Henry David Thoreau – who, incidentally, was born this day, 1817 – decided to go off the grid. Granted, there was no “grid” at the time in the modern sense and he didn’t go very far in any case, but you get the point. Overwhelmed and not a little disgusted with the accoutrements of civilization, Thoreau set out to live a simple life in accord with nature.

In the first chapter of Walden, Thoreau explained:

The very simplicity and nakedness of man’s life in the primitive ages imply this advantage, at least, that they left him still but a sojourner in nature. When he was refreshed with food and sleep, he contemplated his journey again. He dwelt, as it were, in a tent in this world, and was either threading the valleys, or crossing the plains, or climbing the mountain-tops. But lo! men have become the tools of their tools.

Thoreau is the patron saint of all of those who have ever thought about quitting the Internet and lobbing Smartphones into a pond if only we could find one. This means most of us have probably lit a candle to Thoreau at some point in our relentlessly augmented lives.

Within the last few days, stories about the Walden-esque Camp Grounded, sponsored by a group called Digital Detox, have been popping up. Already, you’ve guessed that Camp Grounded was an opportunity to spend some time off the proverbial grid: no cellpones, no tablets, no computers, and no watches.

Writing about the event at Gigamon, Matthew Ingram offered what has by now become a predictable three-step response to these sorts of events or programs, or to most any critique of the Internet or digital devices.

Step 1: Illustrate how similar concerns have always existed. People have felt this way before, etc.*

Step 2: Deconstruct the line between offline and online activity. Online activities are no less “real” or “genuine” than offline activities …**

Step 3: Locate the “real” problem somewhere else altogether. It’s not the Internet, it’s _______________.***

Pivoting on the case of Paul Miller, a writer for Verge who spent a year sans Internet only to discover that there are also analog forms of wasting time, Ingram concluded,

Is it good to disconnect from time to time? Of course it is. And there’s no question that the pace of modern life has accelerated over the past decade, with so many sources of real-time activity that we feel compelled to participate in, either because our friends and family are there or because our jobs require it. But disconnecting from all of those things isn’t going to magically transform us into better people somehow — all it will do is reveal us as we really are.

But here’s the thing. While there are limits to the malleability of our character and personality, who “we really are” is a work in progress. We are now who we have been becoming. And who we are becoming is, in part, a product of habits and dispositions that arise out of our daily actions and practices, including our digitally mediated activities.

The problem with the three step strategy outlined above is that it doesn’t really erase the difference between online and offline experience. While it waves a rhetorical hand to that effect, it nevertheless retains the distinction but dismisses the significance of online experience and digital devices.

But online experience and digital devices, precisely because they are “real,” matter. Ingram is right to say that “disconnecting … isn’t going to magically transform us into better people somehow.” But for some people, under certain conditions, it may in fact be an important step in that direction.

Long before the Internet or even Walden, Aristotle taught that the mean between two excesses was the ideal to aim for. So, between the excesses of gluttony and ascetic deprivation, there was the ideal use of food for both pleasure and nutrition. This ideal use stood between two extremes, but it wasn’t simply a matter of splitting the difference. According to Aristotle, the mean was relative: it depended on each person’s particular circumstances.

But the point wasn’t simpy to hit some artificial middle ground for its own sake — it was to learn how to use things without being used by them. Or, as Thoreau put it, to learn how not to become the tool of our tools.

That’s what we’re looking for in our relationship to the Internet and our digital devices: the sense that we are using them toward good, healthy, and reasonable ends. Instead, many people feel as if they are being used by their devices. The solution is neither reactionary abstinence, nor thoughtless indulgence. What’s more, there’s no one answer for it that is universally applicable. But for some people at some times, taking extended of periods of time away from the Internet may be an important step toward using, rather than being used by it. The three-step rhetorical strategy used to dismiss those who raise questions about our digital practices won’t help at all.

_______________________________________

*Sometimes these historical analogies are misleading, sometimes they are illuminating. Never are they by themselves cause to dismiss present concerns. That would be sort of like saying that people have always been struck by diseases, so we shouldn’t really be too worried about it.

**A lot of pixels have already been spent on this one. E.g., here and here.

***I’ve actually written something similar, but the key is not to lose sight of how devices do play a role in the phenomenon.