“There is a subtle but fundamental difference between finding direction … and ambiently knowing direction.” This was Evgeny Morozov’s recent encapsulation of Tristan Gooley’s The Natural Navigator. According to Gooley, natural navigation, that is navigation by the signs nature yields, is a dying art, and its passing constitutes a genuine loss.

Even if you’ve not read The Natural Navigator, or Morozov’s review, your thoughts have probably already wandered toward the GPS devices we rely on to help us find direction. It’s a commonplace to note how GPS has changed our relationship to travel and place. In “GPS and the End of the Road,” Ari Schulman writes of the GPS user: “he checks first with the device to find out where he is, and only second with the place in front of him to find out what here is.” One may even be tempted to conclude that GPS has done to our awareness of place what cell phones did to our recall of phone numbers.

(Of course, this is not a brief against GPS, much less against maps and compasses and street signs. These have their place, of course. And there are a number of other qualifications which could be offered, but I’ll trust to your generosity as readers and assume that these are understood.)

From the perspective of natural navigation, however, GPS is just one of many technologies designed to help us find our way that simultaneously undermine the possibility that we might also come to know our way or, we might add, our place. Navigational devices, after all, enter into our phenomenological experience of place and do so in a way that is not without consequence.

When I plug an address into a GPS device, I expect one thing: an efficient and unambiguous set of directions to get me from where I am to where I want to go. My attention is distributed between the device and the features of the place. The journey is eclipsed, the places in between become merely space traversed. In this respect, GPS becomes a sign of the age in its struggle to consider anything but the accomplishment of ends with little regard for the means by which the ends are accomplished. We seem to forget, in other words, that there are goods attending the particular path by which a goal is pursued that are independent of the accomplishment of that goal.

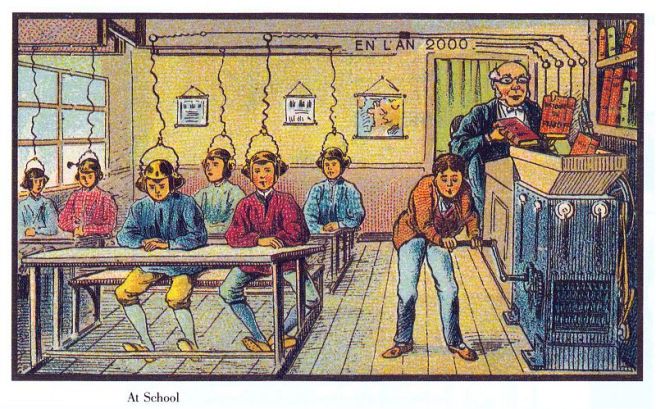

It’s a frame of mind demanded, or to put it in less tech-derministic terms, encouraged by myths of technological progress. If I am to enthusiastically embrace every new technology, I must first come to believe that means or media matter little so long as the end is accomplished. A letter is a call is an email is a text message. Consider this late nineteenth century French cartoon imagining the year 2000 (via Explore):

From our vantage point, of course, this seems silly … but only in execution, not intent. Our more sophisticated dream replaces the odd contraption with the Google chip. Both err in believing that education is reducible to the transfer of data. The means are inconsequential and interchangeable, the end is all that matters, and it is a vastly diminished end at that.

Natural navigation and GPS may both get us where we want to go, but how they accomplish this end makes all the difference. With the former, we come to know the place as place and are drawn into more intimate relationship with it. We become more attentive to the particulars of our environment. We might even find that a certain affection insinuates itself into our experience of the place. Affective aspects of our being are awakened in response. When a new technology promises to deliver greater efficiency by eliminating some heretofore essential element of human involvement, I would bet that it also effects an analogous alienation. In such cases, then, we have been carelessly trading away rich and rewarding aspects of human experience.

Sometimes it is the road itself that makes all the difference.