In Hitchcock’s 1954 classic, Rear Window, Jimmy Stewart plays a photojournalist named Jeff who is laid up with a broken leg and passes his time observing his neighbors through his apartment’s rear window. The window looks out on a courtyard onto which the rear windows of all the other apartments in the building also open up. It’s a multiscreen gallery for Stewart’s character who reclines in the shadows and becomes engrossed in the lives of his neighbors – the attractive dancer, the lonely woman, the young pianist, the newlyweds, and, most significantly, the unhappy married couple. Increasingly playing the part of the obsessive voyeur, he becomes convinced the disgruntled husband murdered his wife. The film’s plot is driven by Jeff’s determination to prove the man’s guilt.

In Hitchcock’s 1954 classic, Rear Window, Jimmy Stewart plays a photojournalist named Jeff who is laid up with a broken leg and passes his time observing his neighbors through his apartment’s rear window. The window looks out on a courtyard onto which the rear windows of all the other apartments in the building also open up. It’s a multiscreen gallery for Stewart’s character who reclines in the shadows and becomes engrossed in the lives of his neighbors – the attractive dancer, the lonely woman, the young pianist, the newlyweds, and, most significantly, the unhappy married couple. Increasingly playing the part of the obsessive voyeur, he becomes convinced the disgruntled husband murdered his wife. The film’s plot is driven by Jeff’s determination to prove the man’s guilt.

The film came to my attention again when I received a link to the clip below, which impressively and artfully splices all of the scenes depicting what Jeff sees out of his window. [Update: The video is no longer available.] Serendipitously, I watched the clip not long after reading some comments on Hans-Georg Gadamer’s hermeneutical aesthetics developed in Truth and Method. Naturally, I then thought of Facebook … as one does after watching Hitchcock and reading Gadamer.

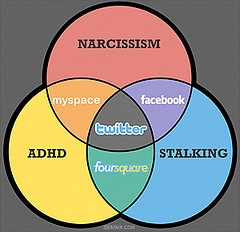

Let’s start with Hitchcock. Like the windows in Hitchcock’s film, Facebook profiles offer an opening into a life and one through which others can observe without the observed knowing it. This is classic Facebook behavior. The platform has always abetted and elicited stalker-ish activity from users. This is why one of the most popular of the many spam links that circulate on the social network purports to reveal who has been looking at your profile. If ever such a capability were enabled it would likely lead to a massive reduction in page views for Facebook.

Like Jeff’s character, Facebook users look through the profiles-as-windows at the lives of their virtual neighbors. And as with Jeff, it may begin in a relatively innocent curiosity born of boredom, or it may veer into the obsessive. There is, of course, one glaring difference between the rear windows and Facebook profiles: Stewart’s neighbors were presumably unaware that they were being watched. Facebook users are not only aware they are being watched – they are counting on it.

On Facebook we’re all flâneurs, simultaneously watching and being watched. But we don’t exactly know who is doing the watching and how much watching they’re doing or to what end. The uncanny moment in Rear Window comes when the watcher becomes the watched. Needless to say, such a moment would be equally uncanny where it to unfold online. Yet it is enough that we know we are being watched in general. This alone renders the profile something other than a representation of our life. It becomes itself a presentation. And that is were Gadamer first comes in.

On Facebook we’re all flâneurs, simultaneously watching and being watched. But we don’t exactly know who is doing the watching and how much watching they’re doing or to what end. The uncanny moment in Rear Window comes when the watcher becomes the watched. Needless to say, such a moment would be equally uncanny where it to unfold online. Yet it is enough that we know we are being watched in general. This alone renders the profile something other than a representation of our life. It becomes itself a presentation. And that is were Gadamer first comes in.

As he develops his hermeneutical aesthetics, Gadamer challenges the representational view of the work of art that understands the work of art as a mere re-presentation of some real thing. On this view, whatever meaning the work of art holds is derivative of the thing it re-presents. Against this view, Gadamer contends that the appearing of the work of art before the participant (for the one who takes in a work of art is never merely a passive observer) constitutes an “event of being.” Meaning inheres in the work of art in itself. It is a presentation, not a re-presentation.

Now think again about a Facebook profile. It may be tempting to understand a profile as a representation of a life or of a personality whose meaning derives from the lived experience of the user who creates the profile. But is this entirely true? It is certainly the case that the online profile is, in a certain sense, grounded in the offline experience of the user. Also, we would do well to resist a digital dualism that abstracts the “real,” offline experience from “virtual,” online experience. Offline and online experience impinge upon one another; it would be misleading to compartmentalize the two.

Yet, there are multiple ways of construing the nature of their enmeshment. One way of resisting digital dualism is to note how the possibility of self-documentation asserts itself in lived experience. I’ve discussed this here on more than a few occasions and Nathan Jurgenson’s notion of “Facebook Eye” captures this dynamic neatly. On this view online profiles impinge upon offline experience by reordering our conscious intentionality – to the person with a social media profile, experience becomes a field of potential self-documentation to be publicized through social media. To the person with a hammer, everything looks like a nail. To the person with a Facebook profile, everything looks like a potential status update. Or alternatively, to the person with a Facebook profile, the question is always “How many ‘likes’ will this get?” But Gadamer offers another complimentary construal.

It begins by noting the presentational character of the online profile. It is not a mere copy of the original life; in its appearing before a profile viewer, it appears on its own terms. It’s meaning is not merely derived from the manner in which it copies life, rather it emerges out of the dynamics of the life as it is presented in the profile. And here is why, as I see it, this does not constitute a digital dualism. Gadamer’s discussion of the work of art as an “event of being” includes what Peter Leithart has called “retroactive ontological consequences” for the thing it refers to in the “real” world.

Leithart interprets Gadamer by reference to landscape painting. When a landscape is painted by Constable, its character has been altered, it is now a “landscape-that-inspires-painting.” When person maintains an online profile, they are now a person-with-a-profile. The landscape painting, Leithart continues, is an “event of being” because it is “an enhancement of the thing itself.” Likewise the online profile, although perhaps enhancement is not necessarily the best word to use here. Moreover Leithart concludes, “every encounter with the real landscape involves a moment of interpretation that is a ‘performance’ of the thing, and after Constable (even for many who are not directly aware of Constable) the interpretive performance is inflected by Constable’s work …” Translated: every encounter with a person-with-a-profile invites acts of interpretation that are inflected by Facebook. Now back to Rear Window to illustrate.

In the film, the windows presented a slice of a life. What Jeff saw was not something other than the lived experience of the people he watched, but the windows did the work of constituting those slices of their lives as something in themselves for Jeff inviting interpretation, not unlike the way a profile presents itself as something in itself for the viewer also inviting the viewer into a work of interpretation. And as we noted, via Gadamer, as a thing in itself the window-as-presentation gives off meaning that has retroactive ontological consequences. If Jeff were to meet any of the people he watched outside of their apartments, his interactions with them would be contoured by his interpretations of their fenestrated (when would I ever have another chance of using that word) presentations.

Likewise, when Facebook users encounter one another offline, their mutual interpretations of one another are loaded with whatever interpretations their profiles have already invited.

Now one final thought. Our presentations always produce more meaning than we intend. This is another way of saying that we are not entirely in control, despite our best efforts, of the manner in which our profile presentations are interpreted. Because they are always partial re-presentations (insofar as they are alluding back to lived experience), our profiles hide while they reveal and thus invite or even demand acts of creative interpretation. These interpretative surpluses, for better or worse, are those that are then brought to bear on our face-to-face encounters.

___________________________________________

An expanded and revised version of this post appeared at The Medias Res.