Sometimes the most obvious realities are those that slip just below our awareness of things, blending into the background of lived experience, surreptitiously shaping and forming our assumptions, intentions, and actions. These realities are in a sense too big to notice, or better, too pervasive to notice. Their very ordinariness renders them ordinarily invisible.

When we think and talk about technology, particularly digital technologies or the Internet, we tend not to think very much about our bodies. In fact, digital technologies have inspired dreams (or, nightmares) of disembodied existence and uploaded consciousness. Even if we are not quite entertaining the possibility of digital immortality, we do tend to talk about digital technology in language that obscures the body’s presence. The Cloud, the Information Age, virtual reality — each of these terms, and others beside, suggest something ethereal and abstract. In any case, they certainly do not invite us to notice the role our bodies may play in the digital order of things.

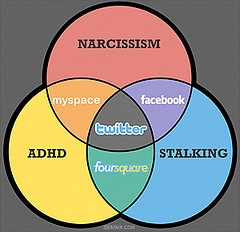

The scholars associated with the website Cyborgology have coined the phrase digital dualism to describe the tendency to abstract the virtual world of bits and data from the “real” world of atoms and stuff when we talk and think about the Internet. I’m sympathetic to their critique of digital dualism. There are different kinds of realities at play, each with their own distinguishing characteristics, but one is not less real than the other and each affects the other in very real ways. Simply put, there is only one reality with digital and material dimensions always informing one another.

But dualisms can be hard to overcome. We like to think in oppositional pairs or binaries. Interestingly, like many of our habits of thought, this may in part be linked to our experience of moving about as bodies in physical space. The world presents itself to us as either here or there, near or far, up or down. As we move about, we are faced with a choice between left and right, backward and forward. And so it may be that digital dualism is built upon a much earlier and more venerable dualism — the old fashioned mind/body variety usually associated with Descartes.

But, consider the following for a moment:

When we update our status on Facebook, we are doing something with our body.

When we send out a tweet, we are doing something with our body.

When we take a picture with our phones, we are doing something with our body.

When we enter and send a text, we are doing something with our body.

When we search the Internet, we are doing something with our body.

And on and on it goes. Our bodies are the one intractable fact that we cannot escape. The body is the ground of being. And I say this while not adhering to philosophical materialism. We may be more than our bodies, but we are certainly not less than our bodies. But we really need not get caught up in metaphysical debates here. What I’m talking about is tangible, not unlike Samuel Johnson’s stone.

Dancers, athletes, craftsmen, and members of liturgical religious communities have an intuitive grasp of the body’s often unnoticed but pervasive influence on the conduct of our everyday lives. Let me illustrate with a personal anecdote or two from the realm of athletics.

A few days ago, when I was getting ready to go running I asked my wife to toss me a shoe that was just out of reach. She did, and without thinking about it, as the shoe was coming toward me, I “trapped” it with my foot using the same gesture I would’ve used to trap a soccer ball. Now it has been a very long time since I’ve played soccer, but that gesture materialized without any conscious thought on my part. It was instinctively activated from a repertoire of possible techniques that my body knew and deployed without my conscious reflection. It became a part of this repertoire by being repeated until it became habitual.

When I played baseball I was a catcher. To this day, some years since I’ve actually caught a game, if I crouch I can feel all sorts of latent bodily “I-cans” coiling up. I can feel the movements of the arm and wrist used to receive a pitch. I can feel exactly what to do if a ball comes in the dirt or if runner breaks for second. These movements are inscribed in me as a form of bodily, non-theoretical know-how. I am told that the experience of professional dancers is similar as is that of craftsmen who have honed an intuitive feel for their work in whatever their medium of specialization. The craftsmen is an especially apt example for our purposes for the way in which tools are implicated in the craftsman’s bodily skill. Finally, consider also the religious believer shaped by a liturgy. For example, the Catholic who crosses themselves reflexively at appropriate moments.

All of this reflects what Henri Bergson called “habit memory.” The temptation may be to minimize this form of memory when compared to our explicit memory of people, events, images, etc. But, returning to my example above, I remember less and less of my soccer games in that sense, while I will never forget how to trap a soccer ball (even if my ability to actually do so wanes significantly over time).

Our ordinary experience in the world is constantly mediated by this kind of embodied, not quite conscious “know-how.” The preeminent philosopher of the body, Merleau-Ponty, called it coping. Hubert Dreyfus, building on Merleau-Ponty, has called it “intelligence without representation.” It is the way in which we are constantly and non-consciously fine-tuning our movements and actions so as to find the best “grip” on reality as we experience it.

Charles Taylor offers this illustration of Merleau-Ponty’s notion of coping, or how we make our way about the world:

“Living with things involves a certain kind of understanding, which we might also call ‘pre-understanding.’ That is, things figure for us in their meaning or relevance for our purposes, desires, activities. As I navigate my way along the path up the hill, my mind totally absorbed anticipating the difficult conversation I’m going to have at my destination, I treat the different features of the terrain as obstacles, supports, openings, invitations to tread more warily or run freely, and so on. Even when I’m not thinking of them, these things have those relevances for me; I know my way about among them.”

The best way to become aware of this dimension of our experience is to think about the moments when it breaks down. My favorite example of this is the Empty Milk Jug Effect. When you pick up an empty milk jug that you think is full, you’re caught off guard; you experience a palpable rupture between non-conscious, embodied judgments and the feedback flowing back through the embodied instantiation of those judgments. The point is that without consciously thinking about it, your body had adjusted itself to find “optimal grip” based on habit memory and when those adjustments proved inadequate you get that sudden sensation of applying way too much force. But what we need to consider is how infrequently this happens. Most of the time our bodies, the world, and our non-conscious thought processes are more or less in sync.

One more example to bring it closer to the realm of digital technology. Since I’ve become habituated to the use of my MacBook, I have an odd experience every once and awhile. Perhaps it’s just me, but I’m willing to bet it’s not. When opening a new window or tab I often begin scrolling with my fingers on the track pad simultaneously with the loading of the page. There are times, however, when there is a slight delay in the opening of the page and I experience a momentary visual disorientation as my eyes move to track with a page that isn’t moving as it should given my habit memory associated with my fingers scrolling on the track pad.

Now at one level this may seem insignificant, but it functions like the tip of an iceberg. It’s a momentary awareness of an immense but ordinarily veiled reality that structures the whole of our experience. (I could be talked down from the scope of that last statement, but I’ll let it stand for now.)

Taylor added that “our grasp of things is not something that is in us, over against the world; it lies in the way we are in contact with the world.” And this brings us to the point: we are in contact with the world through our tools. Our tools, our bodies, our brains, and the world form a circuit of pre-understanding, perception, thinking, and action. A large portion of this circuit is composed of non-conscious habit-memory, and some of that habit-memory is formed through our technologically mediated engagement with the world. The way we use our tools can form habits that sink below the level of consciousness and thereby become part of the pre-understanging through which we navigate experience. And this happens because we use our technologies with our bodies and repeated bodily actions turn into our habit-memory.

We casually (with a nervous laughter) speak of being addicted to the Internet or to Facebook or of panicking when we forget our cell phones. We feel a certain compulsion, but we tend to psychologize this compulsion, that is we render it a mental or emotion disposition. And so it may be, in part. But the compulsions of technology may be less in the mind than in the body. Or better yet, they are anchored in the mind through the body.

Moreover, because our technologies enter into the circuit comprising our engagement with the world, they change the nature of our experience. As we navigate the world, our pre-understanding does not merely recognize objects in themselves within our field of experience. Rather, we perceive objects as they are for-us and how they figure in whatever activity we are engaged in. Our tools then shape how things and experiences appear to be for-us. Having hammer in hand changes how things present themselves; it opens up new possibilities for action that were not present before. For the person with a smartphone, their grasp of things lies in all of the ways the smartphone enables contact with the world. Repeated, embodied activation of these possibilities form habit memories that are then sedimented into the pre-understandings we bring to bear upon experience.

We have formed countless habit memories with our digital technologies, especially as they have become increasingly portable and handheld. We instinctively relate to the world through the capacities and capabilities that we have learned through the embodied use of our tools.

______________________________________________________________

Two related posts:

Technology, Habit, and Being in the World

Technology Use and the Body