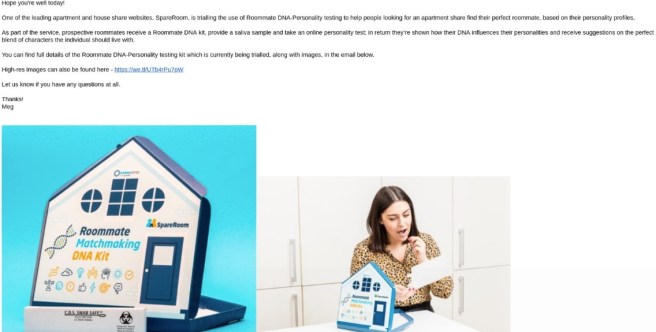

“Prospective roommates receive a Roommate DNA kit, provide a saliva sample and take an online personality test; in return they’re shown how their DNA influences their personalities and receive suggestions on the perfect blend of characters the individual should live with.”

That’s a bit of text taken from the screen shot of an email that Zeynep Tufekci tweeted yesterday. Here’s the the whole thing.

You can read more about the venture here.

Responding to Tufekci, Cathy Davidson commented, “Imagine what scientists of the future (if there IS a future) will say about the ridiculous alchemies of data ‘science’ of the first quarter of the 21st century . . .” To which David Perry replied, “alchemy is a good word choice there. I like phrenology, but I think driving the analogies back a few centuries works too.”

What if, however, we’re not really talking about an analogy, but something more akin to an inherited family resemblance? What if alchemy is more directly and more closely related to what we think of as science and technology?

Historians of science and technology, will confirm that this is exactly the case. The most elegant formulation of this connection is provided by C.S. Lewis, who, while not a historian of science, was, as a scholar of medieval and Renaissance literature, intimately familiar with the relevant intellectual history. In The Abolition of Man, Lewis observed,

I have described as a `magician’s bargain’ that process whereby man surrenders object after object, and finally himself, to Nature in return for power. And I meant what I said. The fact that the scientist has succeeded where the magician failed has put such a wide contrast between them in popular thought that the real story of the birth of Science is misunderstood. You will even find people who write about the sixteenth century as if Magic were a medieval survival and Science the new thing that came in to sweep it away. Those who have studied the period know better. There was very little magic in the Middle Ages: the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are the high noon of magic. The serious magical endeavour and the serious scientific endeavour are twins: one was sickly and died, the other strong and throve. But they were twins. They were born of the same impulse. I allow that some (certainly not all) of the early scientists were actuated by a pure love of knowledge. But if we consider the temper of that age as a whole we can discern the impulse of which I speak.

There is something which unites magic and applied science while separating both from the wisdom of earlier ages. For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For magic and applied science alike the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique ….

Lewis Mumford and Jacques Ellul have made similar observations and drawn similar conclusions.

This connection is important if we are to understand not merely the nature of a given technology but the spirit that animates its creation and renders its adoption plausible or even desirable.

As Heidegger* famously taught, the essence of technology is nothing technological. This is to say that we won’t really understand technology if we focus on discreet technological artifacts. Something that is not, in that sense, technological animates and sustains the particular direction the technological project has taken in the modern societies.

We were closer to the mark, in his view, if we approached the question of technology by the path of revealing. There is a mode of revealing, of making the world appear to us, that arises from and drives the development modern technology. The essence of technology is a way of seeing or construing the world—as standing reserve, as raw material for projects of willful mastery and exploitation—that yields a particular kind of knowledge: instrumental knowledge, or, if you like, weaponized knowledge.

This way of seeing, and the knowledge that flows from it, generates results, but it also locks us into a narrow field of vision, and, perniciously, veils its true nature from us. We fail to grasp that what we see is conditioned and narrowed in this manner; we take it for granted that this is the only way to construe the world. Swaths of experience become invisible or unintelligible to us, the lure of certain kinds of action becomes irresistible, ways of being in the world are foreclosed.

In the passage cited earlier, Lewis, in my view, tracks with Heidegger’s diagnosis (independently so, as far as I know) and draws out an important implication: the reach of this particular way of seeing finally extends to how we understand what it means to be a human being. What begins as a project to subdue nature ends with the subduing of the human being. We become the final frontier of our own making and exploiting. (Lewis points out that what this really means is, of course, the power of a few, Lewis calls them the Conditioners, over the many.)

The impulse to master and the confidence (faith, really) in technique are apparent in the suggestion that a DNA test will help you find the ideal roommate. This example, taken by itself, is rather trivial. Outbursts of enthusiasm around certain techniques emerge and fade throughout the history of technology, and marketers, master technicians themselves, take note. But this is besides the point. The point is that this tool, outlandish as it may still appear to some, partakes of, reveals, and reinforces a pattern that is prior to and more significant than this one technique and the use to which it is put.

Altogether this suggests a useful question or two: Upon what assumptions about human nature does my use of a technology depend? Or, from another direction, What assumptions about human nature does my use of a technology engender?

(A bit more about this in the next installment of The Convivial Society.)

* I grow increasingly uncomfortable making use of Heidegger’s work as it has become clear that his ties to the National Socialists ran deeper than his defenders have argued. Something like Ellul’s verdict seems right: “As early as 1934, Ellul was aware of Heidegger’s political views and concluded, as his long-time interviewer Patrick Troude-Chastenet writes, ‘that someone who made such gross errors of judgment in political thinking could be of no avail to him in his search for an understanding of the world in which we live.'” But for now, there it is. The line is from “The Question Concerning Technology,” which remains a canonical text in the philosophy of technology.

Tip the Writer

$1.00

“Swaths of experience become invisible or [un]intelligible to us” I think you meant.

Always good to see CS Lewis quoted, much undervalued and unappreciated I think. His Perelandra trilogy explores this theme in fiction, especially the final book.

Re Heidegger – it would be good if somewhere I could find an explanation (Heidegger’s own ideally) as to why he supported the NSDP. Do you know of one? (Not a “how awful, Heidegger was a Nazi”). Although if it was Heidegger’s own I don’t imagine I’d be able to understand it.

Thanks for catching that, correction made. And, yes, agreed regarding Lewis. As for Heidegger, this essay was useful: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/is-heidegger-contaminated-by-nazism

Enjoyable piece that moves from roomies to Heidegger!

Pope Francis makes a very similar point in Laudato si (para 107), so if Heidegger is a problem, you can use the pope…

Indeed!

Isn’t then nearly everything alchemy and magic? For example making fire by rubbing two sticks together can be seen as magic or alchemy. Making a simple tea too, is the process of combining water, fire, a container of clay or metal, and plant materials.

Even walking then could be seen as magic. Where the will subdues the material body to make it move around.

Maybe I am understanding wrongly, but it seems to me that without the concept of magic in the context of technology then nothing could ever exist.

Also in the link where you referred to Ellul writing about magic and technique, where he said that spiritual techniques become conformist (always the same rituals, same prayer wheels etc..)

But with this definition wouldn’t literally everything become technology and ritualistic?

For example the sun rises and sets every day. That seems like a very ritualistic and conformist thing, like how Ellul described technology. Or what about DNA? It has repeating patterns of only few molecules. Human beings are usually the same too in form. The same shape of skull, 2 eyes, 2 hands, 2 legs etc.. The same for animals. Dancing, art, music, and culture also uses rituals all the time in repeating the same kinds of patterns and methods.

Again maybe I don’t understand fully. But it feels like that with this world view everything is technology including nature itself and that there really is no hope at all to escape from it’s problems or even think about solutions or alternatives.

Wouldn’t nature just be it’s own unique and original classification? Technology and magic are really just the perversion of what was meant to be something else. Starting a fire or even making tea? Science which benefits people and makes life easier. Media services that not only affect the way you feel, think and then act? Technology and now ritualistic because a majority of people will get their opinions from these “services”(personally why I believe the Television was called a program).

You may not be religious but spiritually there are several accounts of interaction whether good or bad which originally is where we get the basis for our morals from as well.