I started to write a post about a few unhinged reactions to an essay published by Nicholas Carr in this weekend’s WSJ, “Automation Makes Us Dumb.” Then I realized that I already wrote that post back in 2010. I’m republishing “A God that Limps” below, with slight revisions, and adding a discussion of the reactions to Carr.

Our technologies are like our children: we react with reflexive and sometimes intense defensiveness if either is criticized. Several years ago, while teaching at a small private high school, I forwarded an article to my colleagues that raised some questions about the efficacy of computers in education. This was a mistake. The article appeared in a respectable journal, was judicious in its tone, and cautious in its conclusions. I didn’t think then, nor do I now, that it was at all controversial. In fact, I imagined that given the setting it would be of at least passing interest. However, within a handful of minutes (minutes!)—hardly enough time to skim, much less read, the article—I was receiving rather pointed, even angry replies.

I was mystified, and not a little amused, by the responses. Mostly though, I began to think about why this measured and cautious article evoked such a passionate response. Around the same time I stumbled upon Wendell Berry’s essay titled, somewhat provocatively, “Why I am Not Going to Buy a Computer.” More arresting than the essay itself, however, were the letters that came in to Harper’s. These letters, which now typically appear alongside the essay whenever it is anthologized, were caustic and condescending. In response, Berry wrote,

The foregoing letters surprised me with the intensity of the feelings they expressed. According to the writers’ testimony, there is nothing wrong with their computers; they are utterly satisfied with them and all that they stand for. My correspondents are certain that I am wrong and that I am, moreover, on the losing side, a side already relegated to the dustbin of history. And yet they grow huffy and condescending over my tiny dissent. What are they so anxious about?

Precisely my question. Whence the hostility, defensiveness, agitation, and indignant, self-righteous anxiety?

I’m typing these words on a laptop, and they will appear on a blog that exists on the Internet. Clearly I am not, strictly speaking, a Luddite. (Although, in light of Thomas Pynchon’s analysis of the Luddite as Badass, there may be a certain appeal.) Yet, I do believe an uncritical embrace of technology may prove fateful, if not Faustian.

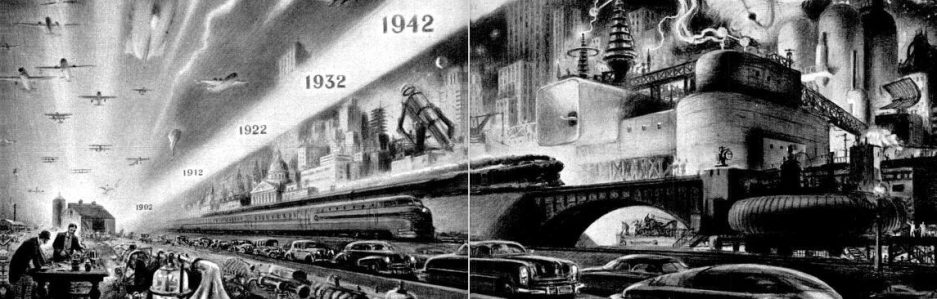

The stakes are high. We can hardly exaggerate the revolutionary character of certain technologies throughout history: the wheel, writing, the gun, the printing press, the steam engine, the automobile, the radio, the television, the Internet. And that is a very partial list. Katherine Hayles has gone so far as to suggest that, as a species, we have “codeveloped with technologies; indeed, it is no exaggeration,” she writes in Electronic Literature, “to say modern humans literally would not have come into existence without technology.”

The stakes are high. We can hardly exaggerate the revolutionary character of certain technologies throughout history: the wheel, writing, the gun, the printing press, the steam engine, the automobile, the radio, the television, the Internet. And that is a very partial list. Katherine Hayles has gone so far as to suggest that, as a species, we have “codeveloped with technologies; indeed, it is no exaggeration,” she writes in Electronic Literature, “to say modern humans literally would not have come into existence without technology.”

We are, perhaps because of the pace of technological innovation, quite conscious of the place and power of technology in our society and in our own lives. We joke about our technological addictions, but it is sometimes a rather nervous punchline. It makes sense to ask questions. Technology, it has been said, is a god that limps. It dazzles and performs wonders, but it can frustrate and wreak havoc. Good sense seems to suggest that we avoid, as Thoreau put it, becoming tools of our tools. This doesn’t entail burning the machine; it may only require a little moderation. At a minimum, it means creating, as far as we are able, a critical distance from our toys and tools, and that requires searching criticism.

And we are back where we began. We appear to be allergic to just that kind of searching criticism. So here is my question again: Why do we react so defensively when we hear someone criticize our technologies?

And so ended my earlier post. Now consider a handful of responses to Carr’s article, “Automation Makes Us Dumb.” Better yet, read the article, if you haven’t already, and then come back for the responses.

Let’s start with a couple of tweets by Joshua Gans, a professor of management at the University of Toronto.

I assume Nicholas Carr used a typewriter to write this. http://t.co/5tyyB0oPUQ

— Joshua Gans (@joshgans) November 23, 2014

I assume Nicholas Carr doesn’t own a dishwashing machine. http://t.co/5tyyB0oPUQ — Joshua Gans (@joshgans) November 23, 2014

Then there was this from entrepreneur, Marc Andreessen:

I, for one, think Nick Carr is very brave to admit technology has turned his analytical thinking skills to mush :-). http://t.co/xSaFoLIvTI

— Marc Andreessen (@pmarca) November 23, 2014

Even better are some of the replies attached to Andreessen’s tweet. I’ll transcribe a few of those here for your amusement.

“Why does he want to be stuck doing repetitive mind-numbing tasks?”

“‘These automatic jobs are horrible!’ ‘Stop killing these horrible jobs with automation!'” [Sarcasm implied.]

“by his reasoning the steam engine makes us weaklings, yet we’ve seen the opposite. so maybe the best intel is ahead”

“Let’s forget him, he’s done so much damage to our industry, he is just interested in profiting from his provocations”

“Nick clearly hasn’t understood the true essence of being ‘human’. Tech is an ‘enabler’ and aids to assist in that process.”

“This op-ed is just a Luddite screed dressed in drag. It follows the dystopian view of ‘Wall-E’.”

There you have it. I’ll let you tally up the logical fallacies.

Honestly, I’m stunned by the degree of apparently willful ignorance exhibited by these comments. The best I can say for them is that they are based on a glance at the title of Carr’s article and nothing more. It would be much more worrisome if these individuals had actually read the article and still managed to make these comments that betray no awareness of what Carr actually wrote.

More than once, Carr makes clear that he is not opposed to automation in principle. The last several paragraphs of the article describe how we might go forward with automation in a way that avoids some serious pitfalls. In other words, Carr is saying, “Automate, but do it wisely.” What a Luddite!

When I wrote in 2010, I had not yet formulated the idea of a Borg Complex, but this inability to rationally or calmly abide any criticism of technology is surely pure, undistilled Borg Complex, complete with Luddite slurs!

I’ll continue to insist that we are in desperate need of serious thinking about the powers that we are gaining through our technologies. It seems, however, that there is a class of people who are hell-bent on shutting down any and all criticism of technology. If the criticism is misguided or unsubstantiated, then it should be refuted. Dismissing criticism while giving absolutely no evidence of having understood it, on the other hand, helps no one at all.

I come back to David Noble’s description of the religion of technology often, but only because of how useful it is as a way of understanding techno-scientific culture. When technology is a religion, when we embrace it with blind faith, when we anchor our hope in it, when we love it as ourselves–then any criticism of technology will be understood as either heresy or sacrilege. And that seems to be a pretty good way of characterizing the responses to tech criticism I’ve been discussing: the impassioned reactions of the faithful to sacrilegious heresy.

perhaps technology advancements at the moment are linked to money

also in everything “we” do there needs to be this harmony with nature or our environment, the squirrels and the owls :) and the little children in our lands and lands far off.

I think until mankind works together to help all of creation then the toys will have to be taken away.

However I strongly believe we are right on the cusp of doing exactly the above. We need only unite Russia with Europe and N. America and we will have world peace. How far it goes beyond that is upto us.

All the tech will come then.

Also, Carr’s newest book “The Glass Cage” tells well-researched, deeper and richer stories why his essay makes sense. The knee jerk reactions to it (the essay) are actually quite humorous.

I taught a college writing course that included work with Carr’s book The Shallows. We spent lots of time discussing the fact that, while Google enables us, it also shapes our thought patterns (oversimplification, but you get the idea). Some of the students were SO very sensitive to any sort of critique of the way they think, work, play, etc, vis-a-vis technology, that they took serious offense and couldn’t really consider Carr’s point. Knee jerk reactions is right. Humorous? Maybe. But a little unsettling too. Sometimes it’s hard to get people to where their perspective will allow “a critical distance from our toys and tools.” We are so entwined with our technology that our toys and tools feel like ourselves…which goes straight to Carr’s point, I suppose.

Very interesting article. I personally think nothing should be above careful, well considered criticism.

Long time ago my father wrote an article in the local newspaper criticizing the irresponsible use of mobile phones. It was the time when the fever of mobile phones was starting. On the next weeks he received angry responses from some readers and a columnist of the same newspaper. My father even received a death threat on our answering machine. So, I know very well what you’re talking about.

Congratulations for your blog. You’re doing a very important mission. Please, excuse for my poor English.

Well said Mike.

I meant to also say that every single time I have lectured or given some kind of seminar on this topic publicly, even in those instances where I have assumed the least critical posture, I have always had at least one or two token responses like those described above. In most cases, more than a few.

Yes. Especially that last paragraph. Some say that sports is our civic religion, but that’s not the case. Technology is. Criticizing it can make one a heretic.

But now I’m thinking about the hardcore anti-technology/hipstery/artisanal/authenticity-obsessed camps. I’m now wondering how to conceptualize that reaction to technology in relation to Technology as Religion.