Doing a little traveling during late May. Posting should pick up again in another week or so.

Cheers!

Today the ArcelorMittal Orbit, an observation tower designed for the Summer Olympics, opened in London. The 377 foot tall structure, England’s tallest work of public art, is part of Olympic Park in Stratford. According to an AP press release, “Some critics have called the ruby-red lattice of tubular steel an eyesore. British tabloids have labeled it ‘the Eye-ful Tower,’ ‘the Godzilla of public art’ and worse.” Its designers, of course, think of it in more flattering terms:

“One of the references was the Tower of Babel. There is a kind of medieval sense to it of reaching up to the sky, building the impossible. A procession, if you like. It’s a long, winding spiral: a folly that aspires to go even above the clouds and has something mythic about it. What I’m interested in is the way 21st century thinking about older technologies allows one to go both forwards and backwards. The form straddles Eiffel and Tatlin.”

Not surprisingly, the Orbit seems to automatically generate comparison to the Eiffel Tower which was constructed for another kind of international gathering/competition, the Exposition Universelle of 1889.

And not unlike the Orbit, the Eiffel Tower also received a mixed reaction:

“We, the writers, painters, sculptors, architects and lovers of the beauty of Paris, do protest with all our vigor and all our indignation, in the name of French taste and endangered French art and history, against the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower.”

Signatories included: Guy de Maupasssant, Alexander Dumas, Emile Zola, Charles Gounod, and Paul Verlaine. But, of course, opinions have mellowed since.

The Eiffel Tower was not the only oversized structure built for a world’s fair. There was also the world’s first ferris wheel standing at 264 feet and offering passengers an awe-inspiring view of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

At the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, best remembered as the site of President William McKinley’s assassination, featured the 375 foot Electric Tower. At a time when many Americans had yet to witness an electrified city-scape, the tower and surrounding buildings became instances of the American technological sublime.

The iconic Space Needle that has come to symbolize the city of Seattle was built for the Century 21 Exposition that was held in 1961.

The two observation towers that comprised part of the New York State Pavilion for the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair still stand today.

“Man’s temples typify his concepts. I cherish the thought that America stands on the threshold of a great awakening. The impulse which this Phantom City will give to American culture cannot be overestimated. The fact that such a wonder could rise in our midst is proof that the spirit is with us.”

— Journalist Fredrick F. Cook, writing of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago

The religion of technology was represented exceptionally well at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. In fact, in the 1939 fair with its “World of Tomorrow” theme, the techno-utopian message of the religion of technology may have found its most compelling medium. Prior to 1939, the American world’s fairs had always been characterized by what Astrid Böger aptly called a “bifocal nature,” that is they “served as patriotic commemorations of central events in American history even as they envisioned the nation’s bright future.” Janus-faced, they looked back on a glorified past and forward toward an idealized future. The fairs of the 1930’s, however, consciously focused their vision on the future. It is true that a glance was still cast backwards – the ‘39 fair for instance commemorated the 250th anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration – but the emphasis was clearly on the wonders that lay ahead.

The ’39 New York fair, in particular, was explicitly eschatological. Its most popular exhibits featured Cities of Tomorrow, Zions that were to be realized through technological expertise deployed by corporate power supported by benign government planning. And little wonder, the nation had been through a decade of economic depression and rumors of war swept across the Atlantic. “To catch the public imagination,” historian David Nye explains, “the fair had to address this uneasiness. It could not do so by mere appeals to patriotism, by displays of goods that many people had no money to buy, or by the nostalgic evocation of golden yesterdays. It had to offer temporary transcendence.” And by the late 1930s, technology appeared to be on the verge of delivering on this promise. “Earlier world’s fairs, in which science had not played so great a role, had also been conceived in utopian spirit,” noted Folke T. Kihlstedt, “but not until the 1930s did science and technology seem to possess the potential for the actualization of a utopian vision.”

While engineers had achieved a place among the clergy of the religion of technology during the late nineteenth century, by the 1930s they had been displaced by the industrial designer who, in Kihlstedt’s phrasing, “quickly became the chief promoter of a utopian future served by the products of technology.” The industrial designer “looked not with the pragmatic eye of the engineer but with the visionary gaze of the utopian.” This “visionary gaze” and the attention to the affective dimension of technology made the industrial designer the ideal prophet of the religion of technology.

The planners of the 1939 New York fair instructed the industrial designers to weave technology throughout the fabric of the whole fair. In previous expositions, science had occupied a prominent but localized place among the multiple exhibits. The 1939 fair intentionally broke with this tradition. “Instead of building a central shrine to house scientific displays,” Robert Rydell explains, “they decided to saturate the fair with the gospel of scientific idealism by highlighting the importance of industrial laboratories in exhibit buildings devoted to specific industries.”

The planners of the 1939 New York fair instructed the industrial designers to weave technology throughout the fabric of the whole fair. In previous expositions, science had occupied a prominent but localized place among the multiple exhibits. The 1939 fair intentionally broke with this tradition. “Instead of building a central shrine to house scientific displays,” Robert Rydell explains, “they decided to saturate the fair with the gospel of scientific idealism by highlighting the importance of industrial laboratories in exhibit buildings devoted to specific industries.”

With nearly a decade of economic depression behind them and a looming international conflagration before them, the fair planners remained committed to the religion of technology and they were intent on creating a fair that would rekindle America’s waning faith. It may not be entirely inappropriate, then, to see the 1939 New York World’s Fair as a revival meeting calling the faithful to repentance and renewed hope in the religion of technology. But the call to renewed faith in 1939 also contained variations on the theme. The presentation of the religion of technology took a liturgical turn and it was alloyed with the spirit of the American corporation.

Ritual Fairs

Historians and critics of the world’s fair have mostly focused their attention on the intention of the fair designers. They have studied the fairs as texts laid out for analysis. But its debatable whether this tells us much about the experience of fairgoers. Warren Susman, writing of 1939 New York World’s Fair, concluded: “The Fair was not open for long,” he noted, “before the people showed both the planners and the commercial interests how perverse they could be about following the arrangements so carefully made for them.” Despite the best efforts of planners, “the people proceeded on its own way.”

Yet for all of this, the fairs were making an impression on fairgoers and Astrid Böger suggests a way of understanding that impression: “world’s fairs are performative events in that they present a vision of national culture in the form of spectacle, which visitors are invited to participate in and, thus, help create.” Writing of the Ferris Wheel at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Böger explains that it was the “striking example of the sensual – primarily visual – experience of the fair, which seems to precede both understanding of the exhibit’s technology and, more importantly, appreciation of it as an American achievement.”

What Böger hones in on in these observations is the distinction between the intellectual content of the fairs as intended by the fair planners and the actual experience of the fairs by those who attended. It is the difference between reading the fairs as a “text” with an explicit message and constructing a meaning through the experience of “taking in” the fair. The planners intended an intellectualized, chiefly cognitive experience. Fairgoers processed the fair in an embodied and mostly affective manner. It is this distinction that leads to the observation that the religion of technology, as it appeared at the fairs, was a liturgical religion. In his articulation of the religion of technology, Noble emphasized the explicit and the propositional. His focus was on belief and theology. But the fairs suggest other dimensions of the religion of technology, practice and ritual.

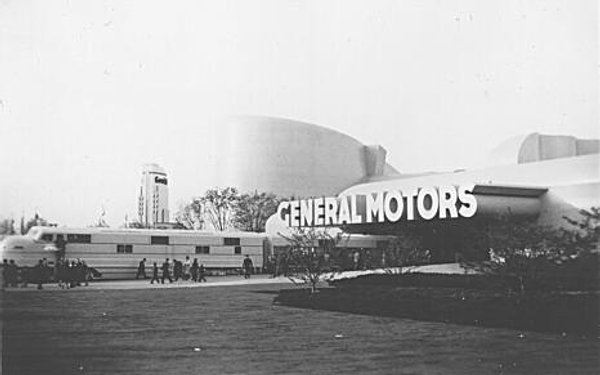

The particular genius of the 1939 New York World’s Fair lay in the manner in which the two most popular exhibits blended their explicit message with a ritual experience. Democracity, housed inside the Perisphere, and General Motors’ Futurama both solved the problem of the impertinent walkers by miniaturizing the idealized world and carefully controlling the fairgoer’s experience of the miniaturized environment. Earlier fairs sought to present themselves as idealized cities, but this risked the diffusion of the message as fairgoer’s crafted their own fair itineraries or otherwise remained oblivious to the implicit messages. Democracity and the Futurama mitigated this risk by crafting not only the world, but the experience itself – by providing a liturgy for the ritual. And the ritual was decidedly aimed at the cultivation of hope in a future techno-utopian society, which is to say it gave ritual expression to the religion of technology.

As David Nye observed, “the most successful [exhibits] were those that took the form of dramas with covertly religious overtones.” In fact, Nye describes the fair as a whole as “a quasi-religious experience of escape into an ideal future equally accessible to all … The fair was a shrine of modernity.” Nowhere was the “quasi-religious” aspect of the fair more clearly evident than in Democracity, the miniature city of the future housed within the fair’s iconic Perisphere.

As David Nye observed, “the most successful [exhibits] were those that took the form of dramas with covertly religious overtones.” In fact, Nye describes the fair as a whole as “a quasi-religious experience of escape into an ideal future equally accessible to all … The fair was a shrine of modernity.” Nowhere was the “quasi-religious” aspect of the fair more clearly evident than in Democracity, the miniature city of the future housed within the fair’s iconic Perisphere.

Fairgoers filed into the sphere and were able to gaze down upon the city of the future from two balconies. When the five and a half minute show began, the narrator began describing the features of this idealized landscape featuring the city of the future at its center. Emanating outward from the central city were towns and farm country. The towns would each be devoted to specific industries and they would be home to both workers and management. As the show progressed and the narrator extoled the virtues of central planning, the lighting in the sphere simulated the passage of day and night. Nye summarizes what followed:

“Once the visitors had contemplated this future world, they were presented with a powerful vision that one commentator compared to ‘a secular apocalypse.’ Now the lights of the city dimmed. To create a devotional mood, a thousand-voice choir sang on a recording that André Kostelanetz had prepared for the display. Movies projected on the upper walls of the globe showed representatives of various professions working, marching, and singing together. The authoritative voice of the radio announcer H. V. Kaltenborn announced: ‘This march of men and women, singing their triumph, is the true symbol of the World of Tomorrow.’”

What they sang was the theme song of the fair that proclaimed:

“We’re the rising tide coming from far and wide

Marching side by side on our way,

For a brave new world,

That we shall build today.”

Kihlstedt suggests Democracity’s designer, Henry Dreyfuss, modeled this culminating scene on Dutch Renaissance artist Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece featuring “a great multitude … of all nations and kindreds, and people” as described in the book of Revelation. “In this well-known painting,” Kihlstedt explains, “the saints converge toward the altar of the Lamb from the four corners of the world. As they reveal the unity and the ‘ultimate beatitude of all believing souls,’ these saints define by their presence a heaven on earth.” Ritual and interpretation were thus fused together in one visceral, affective liturgy. Each visitor experienced a nearly identical presentation, and many did so repeatedly. The message was both explicit and memorable.

Corporate Liturgies

Earlier fairs were driven by a variety of ideologies. Rydell in particular has emphasized the imperial and racial ideologies driving the design of the Victorian Era fairs. These fairs also promoted political ideals and patriotism. Additionally, they sought to educate the public in the latest scientific trends (dubious as they may be in the case of Social Darwinism). But in the 1930s the emphasis shifted decidedly. Böger notes, for example, “the early American expositions have to be placed in the context of nationalism and imperialism, whereas the world’s fairs after 1915 went in the direction of globalism and the ensuing competition of opposing ideological systems rather than of individual nation states.” More specifically the fairs of the 1930s, and the 1939 fair especially, aimed to buttress the legitimacy of democracy and the free market in the face of totalitarian and socialist alternatives.

“From the beginning,” Rydell observes, “the century-of-progress expositions were conceived as festivals of American corporate power that would put breathtaking amounts of surplus capital to work in the field of cultural production and ideological representation.” Kihlstedt likewise notes, “whereas most nineteenth-century utopias were socialist, based on cooperative production and distribution of goods, the twentieth-century fairs suggested that utopia would be attained through corporate capitalism and the individual freedom associated with it.” He added, “the organizers of the NYWF were making quasi-propagandistic use of utopian ideas and imagery to equate utopia with capitalism.” For his part, Nye drew on Roland Marchand to connect the evolution of the world’s fairs with the development of corporate marketing strategies: “corporations first tried only to sell products, then tried to educate the public about their business, and finally turned to marketing visions of the future.” Interestingly, Nye also tied the ritual nature of the fairs with the corporate turn: “Such exhibits might be compared to the sacred places of tribal societies … Each inscribed cultural meanings in ritual … And who but the corporations took the role of the ritual elders in making possible such a reassuring future, in exchange for submission.”

In this way the religion of technology was effectively incorporated. American corporations presented themselves as the builders of the techno-utopian city. With the cooperation of government agencies, the corporations would wield the breathtaking power of technology to create a perfect, rationally planned and yet democratic consumer society. Thus was the religion of technology enlisted by the marketing departments of American corporations.

The major American world’s fairs functioned as microcosms of American society. At the fairs, the ideals of cultural, political, and economic elites are put on display. These ideals were anchored in a mythic past and projected in an equally mythic future. The fairs not only reflected the ideals of American elites, they also registered an indelible impression on the millions of Americans who attended. The precise measure of the influence of the fairs on American society, however, remains difficult to measure. Yet, framing the 1939 New York World’s fair within the larger story of the religion of technology reveals the emergence of a powerful alliance of technology, religious aspirations, and corporate power. This alliance was certainly taking shape before 1939, but at the New York fair it announced itself in memorable and decisive fashion. Through the careful deployment of an imaginative liturgical experience, the fair instilled the virtues of this alliance in a generation of Americans. This generation would go on to build a society that, for better and for worse, reflected the triumph of the incorporated religion of technology.

The title suggested itself to me before I had written a word. I picked up Walter Benjamin’s classic essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,”* and in my mind I heard, “The Self in the Age of Its Digital Reproducibility.” I then read through the essay once more with that title in mind to see if there might not be something to the implied analogy. I think there might be.

The title suggested itself to me before I had written a word. I picked up Walter Benjamin’s classic essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,”* and in my mind I heard, “The Self in the Age of Its Digital Reproducibility.” I then read through the essay once more with that title in mind to see if there might not be something to the implied analogy. I think there might be.

Of course, what follows is not intended as a strict interpretation and reapplication of the whole of Benjamin’s essay. Instead, it’s a rather liberal, maybe even playful, borrowing of certain contours and outlines of his argument. The borrowing is premised on the assumption that there is a loose analogy between the mechanical reproduction of visual works of art enabled by photography and film, and the reproduction of our personality across a variety of networks enabled by digital technology.

At one point in the essay, Benjamin noted, “commentators had earlier expended much fruitless ingenuity on the question of whether photography was an art – without asking the more fundamental question of whether the invention of photography had not transformed the entire character of art …” Just so. We might say commentators have presently expended much fruitless ingenuity asking about whether this or that digital technology achieved the status of this or that prior analog technology without asking the more fundamental question of whether the invention of digital technology had not transformed the entire character of the field in question. The important question is not, for instance, whether Facebook friendship is real friendship, but how social media has transformed the entire character of relationships. So in this fashion we take Benjamin as our guide letting his criticism suggest lines of inquiry for us.

Benjamin’s essay is best remembered for his discussion of the aura that attended an original work of art before the age of mechanical reproduction. That aura, grounded in the materiality of the work of art, was displaced by the introduction of mechanical reproduction.

“What, then, is the aura?” Benjamin asks. Answer: “A strange tissue of space and time: the unique apparition of a distance, however near it may be …” And, he adds, “what withers in the age of the technological reproducibility of the work of art is the latter’s aura.”

Aura, to put it more plainly, is a concept that gathers together the authenticity and authority felt in the presence of a work of art. This authenticity and authority of the work of art fail to survive its mechanical (as opposed to manual) reproduction for two principal reasons:

“First, technological reproduction is more independent of the original than is manual reproduction. For example, in photography it can bring out aspects of the original that are accessible only to the lens … but not to the human eye; or it can use certain processes, such as enlargement or slow motion, to record images which escape natural optics altogether. This is the first reason. Second, technological reproduction can place the copy of the original in situations which the original itself cannot attain. Above all, it enables the original to meet the recipient halfway, whether in the form of a photograph or in that of a gramophone record.”

May we speak of the aura that attends a person in “the here and now,” as Benjamin puts it? I would think so. Benjamin himself suggests as much when he discusses the work of the film actor: “The situation can be characterized as follows: for the first time – and this is the effect of film – the human being is placed in a position where he must operate with his whole living person while forgoing its aura. For the aura is bound to his presence in the here and now. There is no facsimile of the aura.”

The analogy I’ve thus far only alluded to is this. Just as mechanical means of reproduction, such as photography, multiplied and distributed an original work or art, likewise do digital technologies, social media most explicitly, multiply and distribute the self. But in so doing they dissolve the aura that attends the person in the flesh and consequently elicit a quest for authenticity.

Consider again the two reasons Benjamin gave for the eclipse of the aura in the face of mechanical reproduction: the independence of the reproduction and its ability to “place the copy in situations which the original itself cannot attain.” The latter of these is most easily reapplied to the digital reproduction of the self. Our social media profiles, for instance, or Skype to take another example, place the self in (multiple, simultaneous) situations that our embodied self cannot attain. But it is the former that may prove most interesting.

Benjamin’s notion of the aura is intertwined with a certain irreducible distance that cannot be collapsed simply by drawing close. Remember his most straightforward definition of aura: “A strange tissue of space and time: the unique apparition of a distance, however near it may be …” The reason for this is that ordinary human vision, even in drawing close, retains an optical inability to penetrate past a certain point. It can only see what it can see, and a manual reproduction cannot improve on that. But a mechanical reproduction can; it can make visible what would remain invisible to the human eye. Imagine for instance what an extreme photographic close-up might reveal about a human face or how high-speed photography may capture a millisecond in time that ordinary human perception would blur into the larger patterns of movement that the unaided human eye is able to perceive.

“Just as the entire mode of existence of human collectives changes over long historical periods,” Benjamin observed, “so too does their mode of perception.” The point then is this: mechanical reproduction, photographs and film, enabled new forms of perception and these new forms of perception effectively neutralized the aura of the original.

Benjamin neatly summed up this dynamic with the notion of the optical unconscious:

“And just as enlargement not merely clarifies what we see indistinctly ‘in any case,’ but brings to light entirely new structures of matter, slow motion not only reveals familiar aspects of movements, but discloses quite unknown aspects within them … Clearly, it is another nature which speaks to the camera as compared to the eye. ‘Other’ above all in the sense that a space informed by human consciousness gives way to a space informed by the unconscious … it is through the camera that we first discover the optical unconscious …”

The camera, in other words, has the ability to bring to the attention of conscious perception what would ordinarily be perceived only at an unconscious level. Benjamin was explicitly pursuing an analogy to the Freudian unconscious. If you prefer to avoid that association, perhaps the term optical non-conscious would suffice. In this way this way this mode of perception may be elided to the bodily forms of intentionality discussed by Merleau-Ponty that are not quite the products of conscious attention. In any case, the capabilities of mechanical reproduction brought to conscious attention what ordinarily escaped it.

So what is the connection to digital reproductions of the self. Well, we might get at it by identifying what could be called the “social unconscious.” Just as photography and film disclosed a real but ordinarily invisible world, might we not also say that digital reproductions of the self materialize real but otherwise invisible relations and mental or emotional states? What else could be the meaning of the “Like” button or the ability to see a visualization of our history with a friend as chronicled on Facebook? Moreover, interactions that before the age of digital reproduction may have passed between two or three persons, now materialize before many more. And while most such interactions would have soon faded into oblivion when they passed out of memory, in the age of digital reproduction they achieve greater durability as well as visibility.

But what are the consequences? Benjamin can help us here as well.

“To an ever-increasing degree, the work reproduced becomes the reproduction of a work designed for reproducibility.” In an age of digital reproduction, the self we are reproducing is increasingly constructed for maximum reproducibility. We live with an eye to the reproductions we will create which we will create with an eye to their being widely reproduced (read, “shared”).

Benjamin also noted the historic tension “between two polarities within the artwork itself … These two poles are the artwork’s cult value and its exhibition value.” When art was born in the service of magic, the importance of the figures drawn lay in their presence not necessarily their exhibition. By liberating of the work of art from the context of ritual and tradition, mechanical reproduction foregrounded exhibition. In the age of digital reproduction, mere being is incomplete without also being seen. It hasn’t happened if it’s not Facebook official. The private/public distinction is reconfigured for this very reason.

For those keen on registering economic consequences, Benjamin, speaking of the actor before the camera, offers this: “The representation of human beings by means of an apparatus has made possible a highly productive use of the human being’s self-alienation.” Now apply to the person before the apparatus of social-media.

Finally, Benjamin speaking of the human person who will be mechanically reproduced by film, writes:

“While he stands before the apparatus, he knows that in the end he is confronting the masses. It is they who will control him. Those who are not visible, not present while he executes his performance, are precisely the ones who will control it. This invisibility heightens the authority of their control.”

Apply more widely to all who are now engaged in the work of digitally reproducing themselves and cue the quest for authenticity.

____________________________________________________

* I’m drawing on the second version of the essay composed in 1935 and published in Harvard UP’s The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media (2008). According to the editors, this version “represents the form in which Benjamin originally wished to see the work published.”

Marcell Jousse was a pioneering scholar of gesture and orality. He was a younger contemporary and student of Marcel Mauss. During the inter-war years, he published a series of seminal studies on orality and gesture that garnered wide spread recognition. The publication of his first book in 1925, The Rhythmic and Mnemotechnical Oral Style of the Verbo-motors, caused an immediate sensation and earned him a series of prestigious posts in Paris, including a stint at the Sorbonne. However, shortly after his death in 1961, Jousse’s work fell into relative obscurity. Because his work is only recently finding its way into English translation, thanks largely to the efforts of Edgard Richard Sienaert, he is little known in the English-speaking world. (To get a feel for how little known, take a look at his Wikipedia page). But his work did not escape notice altogether. It features prominently in Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy.

Ong advanced a simple, yet profound thesis: “writing restructures consciousness.” As Ong traced the antecedents of his thesis, which was largely the synthesis of a substantial body of existing work, he acknowledged a debt to Jousse’s distinction, based on his rural upbringing and extensive field work in the Middle East, between “oral composition” and “written composition.” Further on, Ong succinctly summarized Jousse’s larger theoretical framework:

“Protracted orally based thought, even when not in formal verse, tends to be highly rhythmic, for rhythm aids recall, even physiologically. Jousse has shown the intimate linkage between rhythmic oral patterns, the breathing process, gesture, and the bilateral symmetry of the human body in ancient Aramaic and Hellenic targums …”

Ong also deployed Jousse’s formulation, verbomotor, to designate cultures that “retain enough oral residue to remain significantly word-attentive in a person-interactive context (the oral type of context) rather than object-attentive.” It may not be entirey unreasonable to suggest that Ong’s work is in large part an elaboration of Jousse’s research. And, while I haven’t done the research to confirm this, I’m willing to bet that somewhere along the line he played part in the thought of Marshall McLuhan.

Not unlike McLuhan, Jousse’s method and writing was controversial, and in some respects ahead of his time. Here is Sienaert’s description of his fist book which was at the time was termed “The Jousse Bomb” (I’m not making that up):

“The Oral Style is a most unusual book. Jousse had read some five thousand books from a bewildering variety of disciplines. From these, he selected five hundred pertinent to his topic, and from them he chose extracts which reflected in some way his observations, which he linked by his own bracketed words, sentences and paragraphs. He thus recycled old materials, building a new house from old bricks, following his own research injunction: The aim of research is to quest for and discover fresh insights and understanding. But how can we discover something fresh and new when it appears as if all has already been discovered? By the incessant, meticulous and detailed scrutiny of the Old.”

Ivan Illich also drew on Jousse in his study of medieval cultures of reading, In the Vineyard of the Text. Illich was particularly impressed by Jousse’s work on psychomotor reading techniques employed in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic settings. Memorization in these contexts was construed as a fully embodied rather than strictly mental activity. Illich noted that the content of sacred texts was memorized “through careful attention paid to the psychomotor nerve impulses which accompany the sentences being learned.” In Koranic and Jewish schools, students read aloud as they swayed and rocked back and forth and in this way were able to later “re-evoke” the text through the activation of those same body movements. In this analysis, Illich is explicitly drawing on research conducted by Jousse:

“Marcel Jousse has studied these psychomotor techniques of fixing a spoken sequence in the flesh. He has shown that for many people, remembrance means the triggering of a well-established sequence of muscular patterns to which the utterances are tied. When the child is rocked during a cradle song, when the reapers bow to the rhythm of a harvest song, when the rabbi shakes his head while he prays or searches for the right answer, or when the proverb comes to mind only upon tapping for a while — according to Jousse, these are just a few examples of a widespread linkage of utterance and gesture. Each culture has given its own form to this bilateral, dissymmetric complementarity by which sayings are graven right and left, forward and backward into trunk and limbs, rather than just into the ear and the eye.”

Ong’s and Illich’s concerns overlap with, but do not encompass the scope of Jousse’s ambitious anthropological project. Jousse developed a cosmological, mimetic theory of human communication. The universe, according to Jousse, impresses itself upon human beings. In fact, it impresses itself on all objects and organisms. The whole of reality is acting and acted upon. Human beings, however, not only receive this impression; they also act out the impression they have received, and this acting out is originally gestural. Sienaert summarizes:

“Man thus first relates to the world which imposes upon him the play of actual experiences. But this is not a passive process: on reception of reality, man is also animated by an energy that is released and that makes him react in the form of gestures.”

Moreover, human beings are uniquely capable of not only responding in their gestures to the impressions of reality, they are capable of re-playing or re-presenting those impressions. In other words, they can remember, they have memories. And before the advent of language, these memories were carried in the body. The transition from gestural to spoken language marks, in Jousse’s view, the transition from anthropology to ethnology. Generic humanity is particularized through the conventional language into which they are socialized.

Yet, even after this transition, the gestural foundations of communication and response to the universe remain embedded in the human being. These underlying structuring principles reveal themselves in what Jousse termed “the oral style.” The oral style is encapsulated in three laws summarized as follows by Sienaert:

1. Le rythmo-mimisme: the law of rhythmo-mimicry. Man is a mimic, he receives, registers, plays, and replays his actual experiences; as movement is possible in sequence only, mimicry is necessarily linked with rhythm.

2. Le bilatéralisme: the law of bilateralism. Man can only express himself in accordance with his physical structure which is bilateral—left and right, up and down, back and forth—and like his global and manual expression, his verbal expression will tend to be bilateral, to balance symmetrically, following a physical and physiological need for equilibrium …

3. Le formulisme: the law of formulism. The biological tendency towards the stereotyping of gestures creates habit, which ensures immediate, easy and sure replay; it is a facilitating psycho-physiological device as it organizes the intussusceptions and the mnesic replay in automatisms—acquired devices necessary to a firm basis for action …

In formulating these laws, based on his study of oral cultures, Jousse came strikingly close to the most prominent contours of the phenomenological account of the body’s role in human perception developed independently by the tradition of thought spanning Husserl and Merleau-Ponty. These laws, in other words, may be understood to govern not only verbal expression, but also embodied experience as a whole.