I’ve been of two minds with regards to the usefulness of the word technology. One of those two minds has been more or less persuaded that the term is of limited value and, worse still, that it is positively detrimental to our understanding of the reality it ostensibly labels. The most thorough case for this position is laid out in a 2010 article by the historian of technology Leo Marx, “Technology: The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept.”

Marx worried that the term technology was “peculiarly susceptible to reification.” The problem with reified phenomenon is that it acquires “a ‘phantom-objectivity,’ an autonomy that seems so strictly rational and all-embracing as to conceal every trace of its fundamental nature: the relation between people.” This false aura of autonomy leads in turn to “hackneyed vignettes of technologically activated social change—pithy accounts of ‘the direction technology is taking us’ or ‘changing our lives.’” According to Marx, such accounts are not only misleading, they are also irresponsible. By investing “technology” with causal power, they distract us from “the human (especially socioeconomic and political) relations responsible for precipitating this social upheaval.” It is these relations, after all, that “largely determine who uses [technologies] and for what purposes.” And, it is the human use of technology that makes all the difference, because, as Marx puts it, “Technology, as such, makes nothing happen.”[1]

As you might imagine, I find that Marx’ point compliments a critique of what I’ve called Borg Complex rhetoric. It’s easier to refuse responsibility for technological change when we can attribute it to some fuzzy, incohate idea of technology, or worse, what technology wants. That latter phrase is the title of a book by Kevin Kelly, and it may be the best example on offer of the problem Marx was combatting in his article.

But … I don’t necessarily find that term altogether useless or hazardous. For instance, some time ago I wrote the following:

“Speaking of online and offline and also the Internet or technology – definitions can be elusive. A lot of time and effort has been and continues to be spent trying to delineate the precise referent for these terms. But what if we took a lesson from Wittgenstein? Crudely speaking, Wittgenstein came to believe that meaning was a function of use (in many, but not all cases). Instead of trying to fix an external referent for these terms and then call out those who do not use the term as we have decided it must be used or not used, perhaps we should, as Wittgenstein put it, ‘look and see’ the diversity of uses to which the words are meaningfully put in ordinary conversation. I understand the impulse to demystify terms, such as technology, whose elasticity allows for a great deal of confusion and obfuscation. But perhaps we ought also to allow that even when these terms are being used without analytic precision, they are still conveying sense.”

As you know from previous posts, I’ve been working through Langdon Winner’s Autonomous Technology (1977). It was with a modicum of smug satisfaction, because I’m not above such things, that I read the following in Winner’s Introduction:

(1977). It was with a modicum of smug satisfaction, because I’m not above such things, that I read the following in Winner’s Introduction:

“There is, of course, nothing unusual in the discovery that an important term is ambiguous or imprecise or that it covers a wide diversity of situation. Wittgenstein’s discussion of ‘language games’ and ‘family resemblances’ in Philosophical Investigations illustrates how frequently this occurs in ordinary language. For many of our most important concepts, it is futile to look for a common element in the phenomena to which the concept refers. ‘Look and see and whether there is anything common to all.–For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that.'”

Writing in the late ’70s, Winner claimed, “Technology is a word whose time has come.” After a period of relative neglect or disinterest, “Social scientists, politicians, bureaucrats, corporate managers, radical students, as well as natural scientists and engineers, are now united in the conclusion that something we call ‘technology’ lies at the core of what is most troublesome in the condition of our world.”

To illustrate, Winner cites Allen Ginsburg — “Ourselves caught in the giant machine are conditioned to its terms, only holy vision or technological catastrophe or revolution break ‘the mind-forg’d manacles.'” — and the Black Panthers: “The spirit of the people is greater than the man’s technology.”

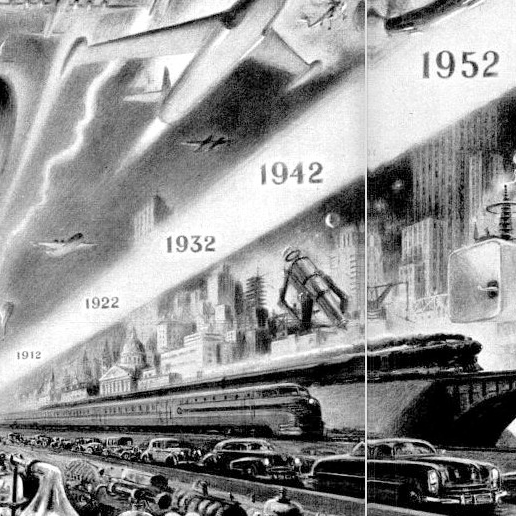

For starters, this is a good reminder to us that we are not the first generation to wrestle with the place of technology in our personal lives and in society at large. Winner was writing almost forty years ago, after all. And Winner rightly points out that his generation was not the first to worry about such matters either: “We are now faced with an odd situation in which one observer after another ‘discovers’ technology and announces it to the world as something new. The fact is, of course, that there is nothing novel about technics, technological change, or advanced technological societies.”

While he thinks that technology is a word “whose time has come,” he is not unaware of the sorts of criticisms articulated by Leo Marx. These criticisms had then been made of the manner in which Jacques Ellul defined technology, or, more precisely, la technique: “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.”

Against Ellul’s critics, Winner writes, “While Ellul’s addition of ‘absolute efficiency’ may cause us difficulties, his notion of technique as the totality of rational methods closely corresponds to the term technology as now used in everyday English. Ellul’s la technique and our technology both point to a vast, diverse, ubiquitous totality that stands at the center of modern culture.”

It is at this point that Winner references Wittgenstein in the paragraph cited above. He then acknowledges that the way in which technology tends to be used leads to the conclusion that “technology is everything and everything is technology.” In other words, it “threatens to mean nothing.”

But Winner sees in this situation something of interest, and here is where I’m particularly inclined to agree with him against critics like Leo Marx. Rather than seek to impose a fixed definition or banish the term altogether, we should see in this situation “an interesting sign.” It should lead us to ask, “What does the chaotic use of the term technology indicate to us?”

Here is how Winner answers that question: “[…] the confusion surrounding the concept ‘technology’ is an indication of a kind of lag in public language, that is, a failure of both ordinary speech and social scientific discourse to keep pace with the reality that needs to be discussed.”There may be a better way, but “at present our concepts fail us.”

Winner follows with a brief discussion of the unthinking polarity into which discussions of technology consequently fall: “discussion of the political implications of advanced technology have a tendency to slide into a polarity of good versus evil.” We might add that this is not only a problem with discussion of the political implications of advanced technology, it is also a problem with discussions of the personal implications of advanced technology.

Winner adds that there “is no middle ground to discuss such things,” we encounter either “total affirmation” or “total denial.” In Winner’s experience, ambiguity and nuance are hard to come by and any criticism, that is anything short of total embrace, meets with predictable responses: “You’re just using technology as a whipping boy,” or “You just want to stop progress and send us back to the Middle Ages with peasants dancing on the green.”[2]

While it may not be as difficult to find more nuanced positions today, in part because of the sheer quantity of easily accessible commentary, it still seems generally true that most popular discussions of technology tend to fall into either the “love it” or “hate it” category.

In the end, it may be that Winner and Marx are not so far apart after all. While Winner is more tolerant of the use of technology and finds that, in fact, its use tells us something important about the not un-reasonable anxieties of modern society, he also concludes that we need a better vocabulary with which to discuss all that gets lumped under the idea of technology.

I’m reminded of Alan Jacobs’ oft-repeated invocation of Bernard Williams’s adage, “We suffer from a poverty of concepts.” Indeed, indeed. It is this poverty of concepts that, in part, explains the ease with which discussions of technology become mired in volatile love it or hate it exchanges. A poverty of concepts short circuits more reasonable discussion. Debate quickly morphs into acrimony because in the absence of categories that might give reason a modest grip on the realities under consideration the competing positions resolve into seemingly subjective expressions of personal preference and, thus, criticism becomes offensive.[3]

So where does this leave us? For my part, I’m not quite prepared to abandon the word technology. If nothing else it serves as a potentially useful Socratic point of entry: “So, what exactly do you mean by technology?” It does, to be sure, possess a hazardous tendency. But let’s be honest, what alternatives do we have left to us? Are we to name every leaf because speaking of leaves obscures the multiplicity and complexity of the phenomena?

That said, we cannot make do with technology alone. We should seek to remedy that poverty of our concepts. Much depends on it.

Of course, the same conditions that led to the emergence of the more recent expansive and sometimes hazardous use of the word technology are those that make it so difficult to arrive at a richer more useful vocabulary. Those conditions include but are not limited to the ever expanding ubiquity and complexity of our material apparatus and of the technological systems and networks in which we are enmeshed. The force of these conditions was first felt in the wake of the industrial revolution and in the ensuing 200 years it has only intensified.

To the scale and complexity of steam-powered industrial machinery was added the scale and complexity of electrical systems, global networks of transportation, nuclear power, computers, digital devices, the Internet, global financial markets, etc. To borrow a concept from political science, technical innovation functions like a sort of ratchet effect. Scale and complexity are always torqued up, never released or diminished. And this makes it hard to understand this pervasive thing that we call technology.

For some time, through the early to mid-twentieth century we outsourced this sort of understanding to the expert and managerial class. The post-war period witnessed a loss of confidence in the experts and managers, hence it yielded the heightened anxiety about technology that Winner registers in the ’70s. Three decades later, we are still waiting for new and better forms of understanding.

______________________________________

[1] I’m borrowing the bulk of this paragraph from an earlier post.

[2] Here again I found an echo in Winner of some of what I had also concluded.

[3] We suffer not only from a poverty of concepts, but also, I would add, from a poverty of narratives that might frame our concepts. See the end of this post.

(1934).