“Man’s temples typify his concepts. I cherish the thought that America stands on the threshold of a great awakening. The impulse which this Phantom City will give to American culture cannot be overestimated. The fact that such a wonder could rise in our midst is proof that the spirit is with us.”

— Journalist Fredrick F. Cook, writing of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago

The religion of technology was represented exceptionally well at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. In fact, in the 1939 fair with its “World of Tomorrow” theme, the techno-utopian message of the religion of technology may have found its most compelling medium. Prior to 1939, the American world’s fairs had always been characterized by what Astrid Böger aptly called a “bifocal nature,” that is they “served as patriotic commemorations of central events in American history even as they envisioned the nation’s bright future.” Janus-faced, they looked back on a glorified past and forward toward an idealized future. The fairs of the 1930’s, however, consciously focused their vision on the future. It is true that a glance was still cast backwards – the ‘39 fair for instance commemorated the 250th anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration – but the emphasis was clearly on the wonders that lay ahead.

The ’39 New York fair, in particular, was explicitly eschatological. Its most popular exhibits featured Cities of Tomorrow, Zions that were to be realized through technological expertise deployed by corporate power supported by benign government planning. And little wonder, the nation had been through a decade of economic depression and rumors of war swept across the Atlantic. “To catch the public imagination,” historian David Nye explains, “the fair had to address this uneasiness. It could not do so by mere appeals to patriotism, by displays of goods that many people had no money to buy, or by the nostalgic evocation of golden yesterdays. It had to offer temporary transcendence.” And by the late 1930s, technology appeared to be on the verge of delivering on this promise. “Earlier world’s fairs, in which science had not played so great a role, had also been conceived in utopian spirit,” noted Folke T. Kihlstedt, “but not until the 1930s did science and technology seem to possess the potential for the actualization of a utopian vision.”

While engineers had achieved a place among the clergy of the religion of technology during the late nineteenth century, by the 1930s they had been displaced by the industrial designer who, in Kihlstedt’s phrasing, “quickly became the chief promoter of a utopian future served by the products of technology.” The industrial designer “looked not with the pragmatic eye of the engineer but with the visionary gaze of the utopian.” This “visionary gaze” and the attention to the affective dimension of technology made the industrial designer the ideal prophet of the religion of technology.

The planners of the 1939 New York fair instructed the industrial designers to weave technology throughout the fabric of the whole fair. In previous expositions, science had occupied a prominent but localized place among the multiple exhibits. The 1939 fair intentionally broke with this tradition. “Instead of building a central shrine to house scientific displays,” Robert Rydell explains, “they decided to saturate the fair with the gospel of scientific idealism by highlighting the importance of industrial laboratories in exhibit buildings devoted to specific industries.”

The planners of the 1939 New York fair instructed the industrial designers to weave technology throughout the fabric of the whole fair. In previous expositions, science had occupied a prominent but localized place among the multiple exhibits. The 1939 fair intentionally broke with this tradition. “Instead of building a central shrine to house scientific displays,” Robert Rydell explains, “they decided to saturate the fair with the gospel of scientific idealism by highlighting the importance of industrial laboratories in exhibit buildings devoted to specific industries.”

With nearly a decade of economic depression behind them and a looming international conflagration before them, the fair planners remained committed to the religion of technology and they were intent on creating a fair that would rekindle America’s waning faith. It may not be entirely inappropriate, then, to see the 1939 New York World’s Fair as a revival meeting calling the faithful to repentance and renewed hope in the religion of technology. But the call to renewed faith in 1939 also contained variations on the theme. The presentation of the religion of technology took a liturgical turn and it was alloyed with the spirit of the American corporation.

Ritual Fairs

Historians and critics of the world’s fair have mostly focused their attention on the intention of the fair designers. They have studied the fairs as texts laid out for analysis. But its debatable whether this tells us much about the experience of fairgoers. Warren Susman, writing of 1939 New York World’s Fair, concluded: “The Fair was not open for long,” he noted, “before the people showed both the planners and the commercial interests how perverse they could be about following the arrangements so carefully made for them.” Despite the best efforts of planners, “the people proceeded on its own way.”

Yet for all of this, the fairs were making an impression on fairgoers and Astrid Böger suggests a way of understanding that impression: “world’s fairs are performative events in that they present a vision of national culture in the form of spectacle, which visitors are invited to participate in and, thus, help create.” Writing of the Ferris Wheel at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Böger explains that it was the “striking example of the sensual – primarily visual – experience of the fair, which seems to precede both understanding of the exhibit’s technology and, more importantly, appreciation of it as an American achievement.”

What Böger hones in on in these observations is the distinction between the intellectual content of the fairs as intended by the fair planners and the actual experience of the fairs by those who attended. It is the difference between reading the fairs as a “text” with an explicit message and constructing a meaning through the experience of “taking in” the fair. The planners intended an intellectualized, chiefly cognitive experience. Fairgoers processed the fair in an embodied and mostly affective manner. It is this distinction that leads to the observation that the religion of technology, as it appeared at the fairs, was a liturgical religion. In his articulation of the religion of technology, Noble emphasized the explicit and the propositional. His focus was on belief and theology. But the fairs suggest other dimensions of the religion of technology, practice and ritual.

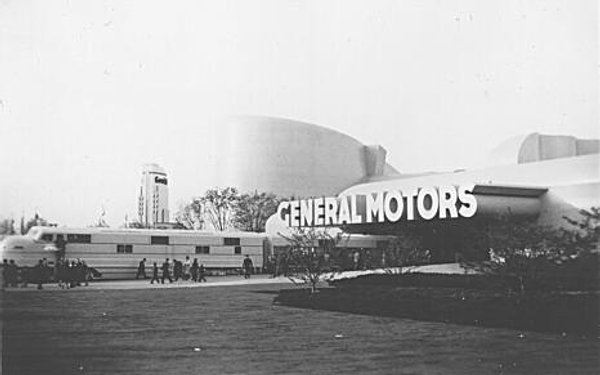

The particular genius of the 1939 New York World’s Fair lay in the manner in which the two most popular exhibits blended their explicit message with a ritual experience. Democracity, housed inside the Perisphere, and General Motors’ Futurama both solved the problem of the impertinent walkers by miniaturizing the idealized world and carefully controlling the fairgoer’s experience of the miniaturized environment. Earlier fairs sought to present themselves as idealized cities, but this risked the diffusion of the message as fairgoer’s crafted their own fair itineraries or otherwise remained oblivious to the implicit messages. Democracity and the Futurama mitigated this risk by crafting not only the world, but the experience itself – by providing a liturgy for the ritual. And the ritual was decidedly aimed at the cultivation of hope in a future techno-utopian society, which is to say it gave ritual expression to the religion of technology.

As David Nye observed, “the most successful [exhibits] were those that took the form of dramas with covertly religious overtones.” In fact, Nye describes the fair as a whole as “a quasi-religious experience of escape into an ideal future equally accessible to all … The fair was a shrine of modernity.” Nowhere was the “quasi-religious” aspect of the fair more clearly evident than in Democracity, the miniature city of the future housed within the fair’s iconic Perisphere.

As David Nye observed, “the most successful [exhibits] were those that took the form of dramas with covertly religious overtones.” In fact, Nye describes the fair as a whole as “a quasi-religious experience of escape into an ideal future equally accessible to all … The fair was a shrine of modernity.” Nowhere was the “quasi-religious” aspect of the fair more clearly evident than in Democracity, the miniature city of the future housed within the fair’s iconic Perisphere.

Fairgoers filed into the sphere and were able to gaze down upon the city of the future from two balconies. When the five and a half minute show began, the narrator began describing the features of this idealized landscape featuring the city of the future at its center. Emanating outward from the central city were towns and farm country. The towns would each be devoted to specific industries and they would be home to both workers and management. As the show progressed and the narrator extoled the virtues of central planning, the lighting in the sphere simulated the passage of day and night. Nye summarizes what followed:

“Once the visitors had contemplated this future world, they were presented with a powerful vision that one commentator compared to ‘a secular apocalypse.’ Now the lights of the city dimmed. To create a devotional mood, a thousand-voice choir sang on a recording that André Kostelanetz had prepared for the display. Movies projected on the upper walls of the globe showed representatives of various professions working, marching, and singing together. The authoritative voice of the radio announcer H. V. Kaltenborn announced: ‘This march of men and women, singing their triumph, is the true symbol of the World of Tomorrow.’”

What they sang was the theme song of the fair that proclaimed:

“We’re the rising tide coming from far and wide

Marching side by side on our way,

For a brave new world,

That we shall build today.”

Kihlstedt suggests Democracity’s designer, Henry Dreyfuss, modeled this culminating scene on Dutch Renaissance artist Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece featuring “a great multitude … of all nations and kindreds, and people” as described in the book of Revelation. “In this well-known painting,” Kihlstedt explains, “the saints converge toward the altar of the Lamb from the four corners of the world. As they reveal the unity and the ‘ultimate beatitude of all believing souls,’ these saints define by their presence a heaven on earth.” Ritual and interpretation were thus fused together in one visceral, affective liturgy. Each visitor experienced a nearly identical presentation, and many did so repeatedly. The message was both explicit and memorable.

Corporate Liturgies

Earlier fairs were driven by a variety of ideologies. Rydell in particular has emphasized the imperial and racial ideologies driving the design of the Victorian Era fairs. These fairs also promoted political ideals and patriotism. Additionally, they sought to educate the public in the latest scientific trends (dubious as they may be in the case of Social Darwinism). But in the 1930s the emphasis shifted decidedly. Böger notes, for example, “the early American expositions have to be placed in the context of nationalism and imperialism, whereas the world’s fairs after 1915 went in the direction of globalism and the ensuing competition of opposing ideological systems rather than of individual nation states.” More specifically the fairs of the 1930s, and the 1939 fair especially, aimed to buttress the legitimacy of democracy and the free market in the face of totalitarian and socialist alternatives.

“From the beginning,” Rydell observes, “the century-of-progress expositions were conceived as festivals of American corporate power that would put breathtaking amounts of surplus capital to work in the field of cultural production and ideological representation.” Kihlstedt likewise notes, “whereas most nineteenth-century utopias were socialist, based on cooperative production and distribution of goods, the twentieth-century fairs suggested that utopia would be attained through corporate capitalism and the individual freedom associated with it.” He added, “the organizers of the NYWF were making quasi-propagandistic use of utopian ideas and imagery to equate utopia with capitalism.” For his part, Nye drew on Roland Marchand to connect the evolution of the world’s fairs with the development of corporate marketing strategies: “corporations first tried only to sell products, then tried to educate the public about their business, and finally turned to marketing visions of the future.” Interestingly, Nye also tied the ritual nature of the fairs with the corporate turn: “Such exhibits might be compared to the sacred places of tribal societies … Each inscribed cultural meanings in ritual … And who but the corporations took the role of the ritual elders in making possible such a reassuring future, in exchange for submission.”

In this way the religion of technology was effectively incorporated. American corporations presented themselves as the builders of the techno-utopian city. With the cooperation of government agencies, the corporations would wield the breathtaking power of technology to create a perfect, rationally planned and yet democratic consumer society. Thus was the religion of technology enlisted by the marketing departments of American corporations.

The major American world’s fairs functioned as microcosms of American society. At the fairs, the ideals of cultural, political, and economic elites are put on display. These ideals were anchored in a mythic past and projected in an equally mythic future. The fairs not only reflected the ideals of American elites, they also registered an indelible impression on the millions of Americans who attended. The precise measure of the influence of the fairs on American society, however, remains difficult to measure. Yet, framing the 1939 New York World’s fair within the larger story of the religion of technology reveals the emergence of a powerful alliance of technology, religious aspirations, and corporate power. This alliance was certainly taking shape before 1939, but at the New York fair it announced itself in memorable and decisive fashion. Through the careful deployment of an imaginative liturgical experience, the fair instilled the virtues of this alliance in a generation of Americans. This generation would go on to build a society that, for better and for worse, reflected the triumph of the incorporated religion of technology.