This is the third in a series of posts discussing the work of a handful of scholars exploring the historical relationship between Christianity and technology. First and second post.

Lynn White further developed his thesis in a long 1971 article, “Cultural Climates and Technological Advance in the Middle Ages,” in which he directly set out to identify the sources of the unprecedented “technological thrust of the medieval West.”

White begins by discussing medieval Europe’s propensity for borrowing and elaborating on technologies initially developed in other societies. The culture of medieval Europe “was unique in the receptivity of its climate to transplants” and this accounts in part for the vigor of medieval technological output. However, this receptivity is itself in need of explanation and in response White reaffirms the logic of “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis”:

“What a society does about technology is influenced by casual borrowings from other cultures, although the extent and uses of these borrowings are reciprocally affected by attitudes toward technological change. Fundamentally, however, such attitudes depend upon what people in a society think about their personal relation to nature, their destiny, and how it is good to act. These are religious questions.”

In what follows, White amplifies and augments the lines of argument adumbrated in the earlier essay while also drawing out additional lines of evidence in support of his thesis. The seminal work of medieval historian Ernst Benz, whose writing on the subject had appeared in Italian in 1964 and was presented in English in 1966, is introduced into White’s argument for the first time. Benz’s study of Zen Buddhism’s “anti-technological impulses” led him to locate Western Europe’s embrace of technological change in its religious outlook. He pointed to Christianity’s linear conception of history, its presentation of God as architect and potter, its theological affirmation of the goodness of material creation, and its presupposition of the “intelligent craftsmanship” of the created order — all in his view unique to Christianity — as the components of what White terms a “cultural climate” remarkably hospitable to technological advance.

White affirms the contours of Benz analysis, but he finds room for improvement. Drawing on two articles independently published in 1956, White once again points to the disenchantment of nature supposedly accomplished by Christianity’s cultural triumph over ancient paganism. He also reaffirms and further develops the importance of the distinction between Latin and Eastern Christianity. Here White strengthens his earlier observations by drawing on iconographic and textual evidence.

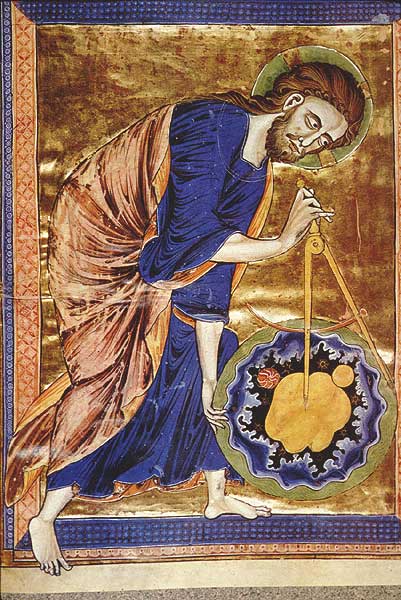

Beginning shortly after the turn of the first Christian millennium, Western iconography depicts God in the act of creation as a builder, master craftsman, and later a mechanic — it was a visual tradition never adopted in the Eastern churches. Exegetically, White points to the Western and Eastern interpretations of the story of Martha and Mary in Luke’s gospel. While a surface reading suggests an endorsement of contemplation over activism, Latin interpreters, beginning with Augustine, go out of their way to soften and even reverse the apparent critique of activism and labor.

With this White then draws in what will become another key locus of attention in subsequent discussions of technology and Christianity: the attitude toward labor in the monastic orders, particularly the Benedictines. White notes that in the Byzantine world, which, unlike the West, did not suffer a general collapse of culture, the religious orders were not forced to bear the burden of sustaining all aspects of civilization, secular and religious. In the West, however, following the collapse of Roman authority, the religious orders, notably the Benedictines, found themselves in the position of performing both religious and secular duties, of uniting worship and labor. This commitment to labor and the mechanical arts would, in White’s view, generate a uniquely religious impetus for the development of technology.

White supports his contention by drawing on the work of the pseudonymous Theophilus and Hugh of Saint Victor. Theophilus’ work, dating from the early 12th century, provides an indispensable record of the era’s technological knowledge while attesting to the religiously motivated technical innovation that White takes to be characteristic of the age. Meanwhile, Theophilus’ contemporary, Hugh of Saint Victor incorporated the mechanical arts into his influential classification of knowledge and the arts. While the mechanical arts were accorded the lowest place in the hierarchical ranking of the arts, they were nonetheless included and this was no small thing. Together, the work of Theophilus and Hugh supported White’s thesis regarding Western Christianity’s role in shaping Europe’s technological surge in the Middle Ages.

White concludes with one more corroborating piece of iconographic evidence. An illustration of Psalm 63 in the Utrecht Psalter dating from the mid-ninth century features a confrontation by between King David and the Righteous and a much larger force of the ungodly. While the ungodly use a whetstone to sharpen their sword, the godly employ “the first crank recorded outside China to rotate the first grindstone known anywhere.” Clearly, White concludes, “the artist is telling us that technological advance is God’s will.”

While “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis” is cited more often and is more frequently taken as a point of departure, it is in “Cultural Climates and Technological Advance in the Middle Ages” that White most persuasively argues the case for Christianity’s formative influence on the history of technology in Western society. With its inclusion of Ernst Benz’ research and its discussion of Benedictine spirituality, this essay frames the research agenda for subsequent research and discussion.

(Next up: George Ovitt’s challenge to White’s thesis.)