Several months ago I wrote a short post on David Noble’s The Religion of Technology. Having recently revisited the book I thought it would be worthwhile to post about Noble’s work once again, this time with a little more detail.

Noble’s thesis offers an intriguing perspective on the relationship between religion and technology. By tracing their historical entwinement, Noble claimed to expose more than “a merely metaphorical” relationship between the two. Noble intended the designation, religion of technology, “literally and historically, to indicate that modern technology and religion have evolved together and that, as a result, the technological enterprise has been and remains suffused with religious belief.”

Noble is making an important distinction here. It is not uncommon to hear people talk metaphorically about technology in religiously inflected language or to draw analogies between religious practices and technology. As an example consider the poster below for “Login: The Conference of Future Insight” by the New! ad agency (h/t @troy_s). This poster analogically relates religion to technology by taking as its theme, “What will we worship next?” The question implies that we “worship” technology analogously to the worship of the religious believer, or that technology functions analogously to a deity in the life of the believer. This is a perfectly valid and suggestive angle of inquiry. However, it is not exactly what Noble has in mind. He unearths a concrete historical interrelationship between the Western technological project and the Christian tradition. A relationship, incidentally, which Noble hoped could be severed for the benefit of all involved.

According to Noble, the religion of technology constitutes “an enduring ideological tradition that has defined the dynamic Western technological enterprise since its inception.” Consequently, it’s influence is evident not only upon “professed believers and those who employ explicitly religious language,” but also on many for “whom the religious compulsion is largely unconscious, obscured by a secularized vocabulary.” This influence manifests itself in the utopian hopes attached to the technological enterprise and can be traced back to the late Middle Ages. These utopian hopes include the expectation that technology would bring about the perfection of the individual and of society and serve as a vehicle of transcendence.

The religion of technology emerges out of a worldview that posits an original state of perfection that, once lost, must be retrieved. Noble’s narrative traces the manner in which technology came to occupy a central place in this effort to regain the lost paradise. The medieval Christian worldview posited the requisite fallen condition: humanity had, by Adam’s sin, fallen from a state of spiritual and material perfection, and technology’s entanglement with the project of restoring the fallen order begins in an unlikely setting. Within the Benedictine monastic tradition, according to Noble’s interpretation*, work and its tools came to be seen as a means of grace enabling the recovery of mankind’s original perfection. At the dawning of the second millennium, this redemptive view of work and its tools was then joined to an eschatological fervor that anticipated the soon return of Christ and the renewal of the created order. In Noble’s narrative, this fusion was best exemplified by Roger Bacon:

“Having inherited the new medieval view of technology as a means of recovering mankind’s original perfection, Bacon now placed it in the context of millenarian prophecy, prediction, and promise. If Bacon, following Erigena and Hugh of St. Victor, perceived the advance of the arts as a means of restoring humanity’s lost divinity, he now saw it at the same time, following Joachim of Fiore, as a means of anticipating and preparing for the kingdom to come, and as a sure sign in and of itself that that kingdom was at hand.”

Noble goes on to describe the manner in which Christianity’s evangelical and missionary impulse “encouraged exploration, and thereby advanced the arts upon which such exploration depended, including geography, astronomy, and navigation, as well as shipbuilding, metallurgy, and, of course, weaponry.” Francis Bacon – who, Noble notes, “is typically revered as the greatest prophet of modern science” – is the next key figure in the evolution of the religion of technology. Noble, agrees with Lewis Mumford’s insistence that what Bacon advanced was “science as technology.” Bacon had little patience for science that did not issue in application and he suffused his advocacy of science as technology with a very specific theological aim: “the relief of man’s estate” understood as the amelioration of the material consequences of humanity’s fall. While the advent of Protestantism addressed the spiritual consequences of the fall, the scientific revolution underway in Europe was destined to address its material consequences. Both together would result in the re-establishment of the unfallen created order.

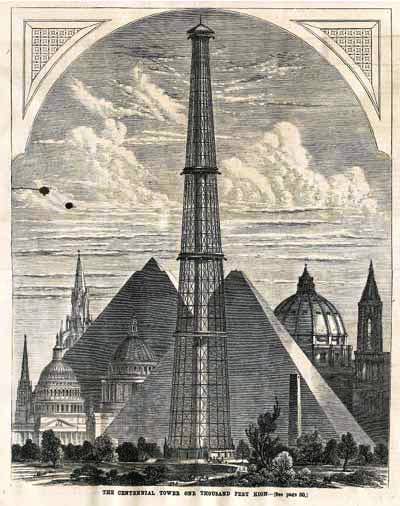

At the end of the nineteenth century, the religion of technology was alive and well in America, and it was best exemplified, according to Noble, by the techno-utopianism of Edward Bellamy whose writings “resound with the familiar refrains of redemption, of the divinely destined recovery of mankind’s lost perfection.” The historian Howard P. Segal, cited by Noble, summarizes Bellamy’s depiction of life in the year 2000 as follows:

The United States of the year 2000 is very much a technological utopia: an allegedly ideal society not simply dependent upon tools and machines, or even worshipful of them, but outright modeled after them. … The purposeful, positive use of technology – from improved factories and offices to new highways and electric lighting systems to innovative pneumatic tubes, electronic broadcasts, and credit cards – is, in fact, critical to the predicted transformation of the United States from living hell into a heaven on earth.

Following his survey of the historical origins of the religion of technology, Noble demonstrates its continuing vitality throughout the twentieth century in chapters exploring atomic weaponry, the space program, artificial intelligence, and genetic engineering. In each of these fields, Noble illustrates the enduring allure of the religiously inspired techno-utopian quest for perfection and transcendence. In the end, Noble concludes that the religion of technology ultimately hinges on a hope of salvation that technology cannot finally provide.

_________________________________________________

*Noble’s interpretation of the Benedictine tradition should be qualified by George Ovitt’s work on the same.