I was reminded of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 a day or two ago while reading Ian Bogost on Apple’s Airpods. Bogost examined Airpods’ potential long term social consequences. “Human focus, already ambiguously cleft between world and screen,” he suggests, “will become split again, even when maintaining eye contact.” A little further on, he writes, “Everyone will exist in an ambiguous state between public engagement with a room or space and private retreat into devices or media.”

It’s a good piece, you should read the whole thing.

It reminded me of Bradbury on two counts. First, and most obviously, Bradbury’s novel imaginatively predicted Airpods before earphones were invented. In the novel they are called Seashells, and they are just one of the ways that characters in the story sever their connection with the world beyond their heads, to borrow Matt Crawford’s formulation. Second, Bogost’s fears echo Bradbury’s. Fahrenheit 451 isn’t really about censorship, after all, and it’s unfortunate that the novel has been reduced to that theme in the popular imagination.

Bradbury makes clear that the firemen who famously start fires to burn books are doing so only long after people stopped reading books of their own accord as other forms of media came to dominate their experience. Actually, to be more precise, they did not stop reading altogether. They stopped reading certain kinds of books: the ones that made demands of the reader, intellectual, emotional, moral demands that might upset their fragile sense of well-being.

Fahrenheit 451, in other words, is more Huxley than Orwell.

Fundamentally, I would argue it is, like Huxley’s Brave New World, about happiness. “Are you happy?” a young girl named Clarisse asks Montag, the protagonist. It is the question that triggers all the subsequent action in the novel. It is the question that awakens Montag to the truth of his situation.

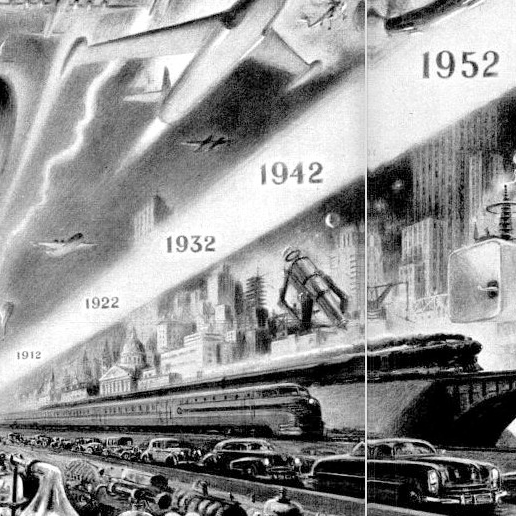

At one remove from the question of happiness, is the matter of alienation from reality effected by media technologies. In 1953, when barely half of American households owned a television set, and primitive sets at that, Bradbury foresaw a future of complete immersion in four wall-sized screens through which people would socialize interactively with characters from popular programs.

Speed also severed people from meaningful contact with the world and became an impediment to thought. Literal speed—billboards where as long as football fields in order to be seen by drivers zooming by and walking was deemed a public nuisance—and the speed of information. An old professor, who knew better but did not have the courage to fight the changes he witnessed, explained the problem to Montag:

“Speed up the film, Montag, quick. Click? Pic? Look, Eye, Now, Flick, Here, There, Swift, Pace, Up, Down, In, Out, Why, How, Who, What, Where, Eh? Uh! Bang! Smack! Wallop, Bing, Bong, Boom! Digest-digests, digest-digest-digests. Politics? One column, two sentences, a headline! Then, in mid-air, all vanishes! Whirl man’s mind around about so fast under the pumping hands of publishers, exploiters, broadcasters, that the centrifuge flings off all unnecessary, time-wasting thought!”

Social media was still more than fifty years away.

This same professor, Faber, later went on to lecture Montag about what was needed. Three things, he claimed. First, quality information, from books or elsewhere. Second, leisure, but not just “off-hours,” which Montag was quick to say he had plenty of:

“Off-hours, yes. But time to think? If you’re not driving a hundred miles an hour, at a clip where you can’t think of anything else but the danger, then you’re playing some game or sitting in some room where you can’t argue with the fourwall televisor. Why? The televisor is ‘real.’ It is immediate, it has dimension. It tells you what to think and blasts it in. It must be, right. It seems so right. It rushes you on so quickly to its own conclusions your mind hasn’t time to protest, ‘What nonsense!'”

The third needful thing? A society that granted “the right to carry out actions based on what we learn from the inter-action of the first two.”

Not a bad prescription, if you ask me.

Earlier in the novel, as Montag travelled by subway to meet Faber for the first, he clung to a copy of the Bible that he had stowed away. He knows he will have to surrender it, so he attempts to memorize as much as he can. But he discovers that his mind is a sieve. He recalled that when he was a child an older relative would play a joke on him by offering a dime if he could fill a sieve with sand.

As he travelled to meet Faber, “he remembered the terrible logic of that sieve.”

But, he thought to himself, “if you read fast and read all, maybe some of the sand will stay in the sieve. But he read and the words fell through, and he thought, in a few hours, there will be Beatty, and here will be me handing this over, so no phrase must escape me, each line must be memorized.”

But his material environment undermined his efforts. As in Kurt Vonnegut’s short story, Harrison Bergeron, distraction undid the work of the mind. In this case, Montag’s focus and concentration battled and lost against the tools of marketing. An ad for Denham’s Dentrifice blared over a loud speaker as he tried to commit what he read to memory. The brief memorable scene portrays a scenario that should feel all-too familiar to us.

He clenched the book in his fists. Trumpets blared.

“Denham’s Dentrifice.”

Shut up, thought Montag. Consider the lilies of the field.

“Denham’s Dentifrice.”

They toil not-

“Denham’s–”

Consider the lilies of the field, shut up, shut up.

“Dentifrice !

“He tore the book open and flicked the pages and felt them as if he were blind, he picked at the shape of the individual letters, not blinking.

“Denham’s. Spelled : D-E-N”

They toil not, neither do they . . .

A fierce whisper of hot sand through empty sieve.

“Denham’s does it!”

Consider the lilies, the lilies, the lilies…

“Denham’s dental detergent.”

“Shut up, shut up, shut up!” It was a plea, a cry so terrible that Montag found himself on his feet, the shocked inhabitants of the loud car staring, moving back from this man with the insane, gorged face, the gibbering, dry mouth, the flapping book in his fist. The people who had been sitting a moment before, tapping their feet to the rhythm of Denham’s Dentifrice, Denham’s Dandy Dental Detergent, Denham’s Dentifrice Dentifrice Dentifrice, one two, one two three, one two, one two three. The people whose mouths had been faintly twitching the words Dentifrice Dentifrice Dentifrice. The train radio vomited upon Montag, in retaliation, a great ton-load of music made of tin, copper, silver, chromium, and brass. The people were pounded into submission; they did not run, there was no place to run; the great air-train fell down its shaft in the earth.

“Lilies of the field.” “Denham’s.”

“Lilies, I said!”

The people stared.

“Call the guard.”

“The man’s off–”

“Knoll View!”

The train hissed to its stop.

“Knoll View!

“Denham’s.” A whisper.

Montag’s mouth barely moved. “Lilies…”

Attention is a resource, and, like all precious resources, it must be cultivated with care and defended. It is, after all, that by which we get our grip on the world and how we remain open to world.

Tip the Writer

$1.00